Middle-class premies find

Middle-class premies find

Oz in the Astrodome

By Ted Morgen

Ted Morgen is a veteran Journalist who lives in New York.

HOUSTON. On Nov. 7, the moon and the planets of Venus, Pluto and Saturn were at right angles, forming what astrologers call the Grand Cross, with Pluto, representing upheaval, in opposition to Saturn, representing

stability. '"the Grand Cross is like a block of pent-up energy, a source of avataric power," astrologer Richard Greer explained. The tailed Kohoutek comet flickered over Houston, announcing, Geer said, ego, death and other

momentous changes in human consciousness. On Nov. 8, Aquarius rose, which meant "the dawn of the Aquarian age in the West." On Nov. 10, Mercury, the planet of the mind, crossed the equator of the sun, which it does every 13

years. "This is the very message of Guru Maharaj ji," Geer said, "the mind being gobbled up by the basic life force. He couldn't have picked a bettet time."

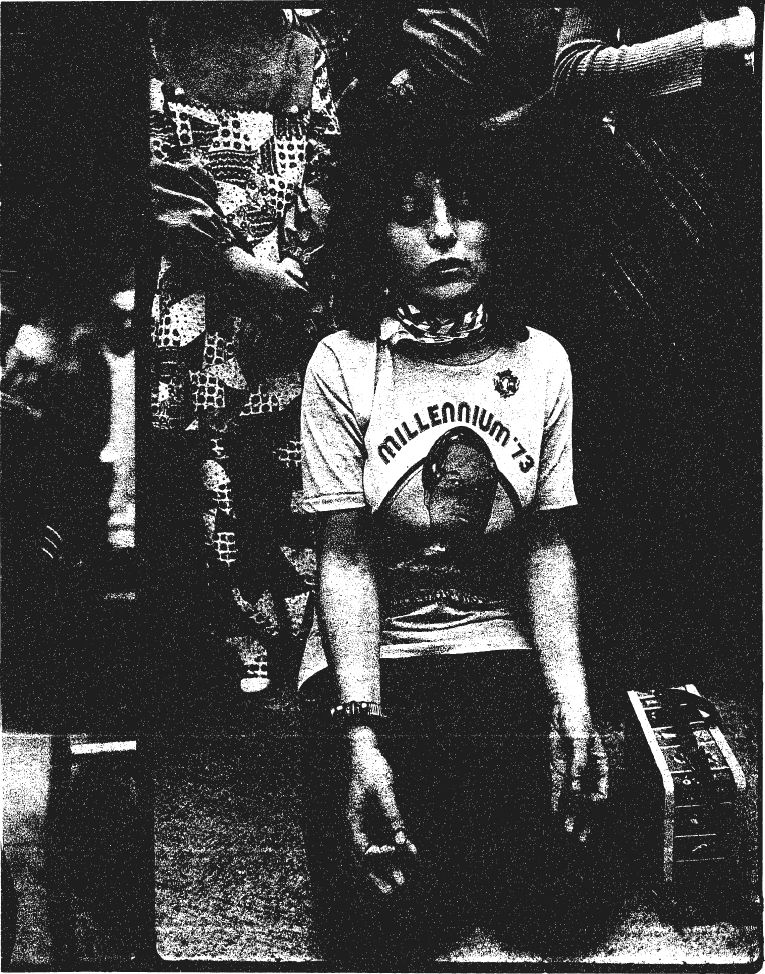

While these auspicious astrological configurations formed in the heavens, a three-day festival called Millennium '73 and billed as "the most significant event in the history of humanity" was taking place in the Houston Astrodome. The Astroturf was covered with red carpeting, and the carpeting was covered with thousands of blissed-out followers of the "perfect master" Guru Maharaj ji, who will be 16 tomorrow.

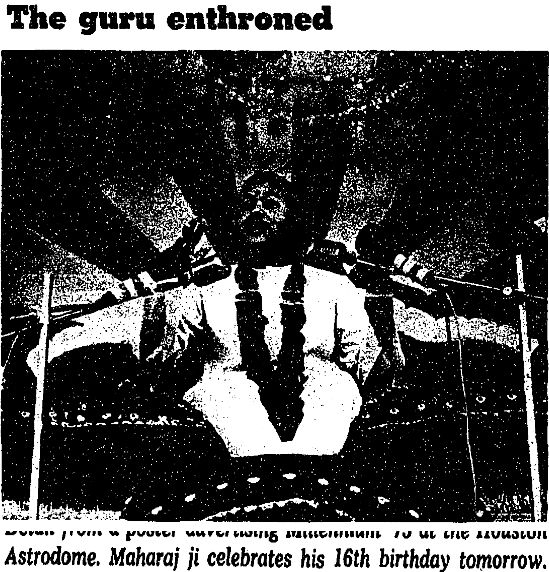

At one end of the Astrodome, where the goal posts are placed for football games, and extending to the 23-yard line, Stood an enormous white plastic stage lit from the inside end divided into seven fern-fringed segments, sprinkled with artificial ponds of cellulose acetate over aluminum foil. One segment was a stage area for plays and dances. Another was a stand for Blue Aquarius, a 56-piece band led by the guru's hulking, cow-eyed brother, 20-year-old Bhole ji.

On a higher, platform sat 24 of the guru's 2,000 mahatmas, or close disciples, all but one of whom are Indian. On the highest platform sat the holy family. The guru's mother, Mata ji, and his two other brothers, 23-year-old Bal Bhagwan ji and l8-year-old Raja ji, were on orange thrones. Three steps up, 300 feet off the ground, sat the guru, as motionless as an ivory Buddha, on a blue velveteen throne with a circular blue Plexiglas back framing his head like a halo. A 14 foot wbite Plexiglas flame, symbol of his pure fire, rose behind him, and a cathode-ray tube projected rainbows on a

(Continued on Page 84)

(Continued from Page 38)

60-foot curtain that hung sail-like over his head.

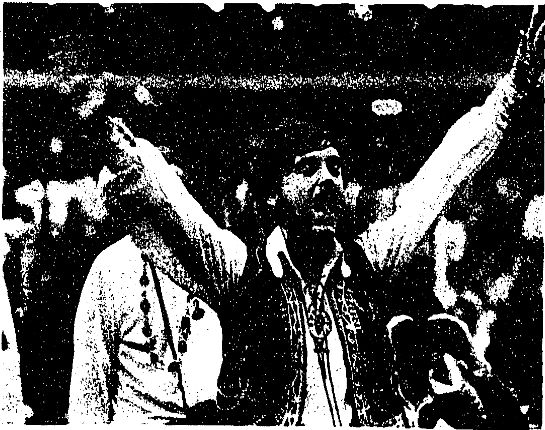

Two 240-foot sound towers each carried 6,000 pounds of equipment so that the guru could be heard. Super-Trooper spotlights lit his round face, and two rear-projection video screens carried his image. When he made his appearance, the $2-million Astrodome scoreboard, with its 1,200 miles of wiring, lit up with his portrait, three rows of WHEN's, and three rows of NOW's. Bhole ji, looking like Bernie Goodman squared in a silver lame tuxedo, tapped his foot and waved his right arm, and the Blue Aquarius opened up with a strong rock beat and its theme song, "O Lord of the Universe."

The Astrodome, which cost $75,000 for three days, had been chosen for both mystical and practical reasons. The guru had a dream that all his followers were under a big dome, and this was the biggest dome available. At the same time, the Astrodome is one of the few nonunion covered stadiums in the country, so that there was no threat of pickets or Union harassment because of volunteer labor.

For with few exceptions, the entire event was staged by the guru's American followers, or premies (an Indian word that means lover of God). Premies drove the trucks and fork lifts, premie doctors ran the clinics, and a premie architect designed the stage. In the adjacent Astrohall, 120 premies stood around plywood tables covered with 25-pound bags of peanut butter, gallon cans of apple butter and loaves of whole wheat bread, and turned out 20,000 sandwiches a day in a seventies version of the multiplication of the loaves.

Depending on the time of day, the Stadium appeared to contain between 15,000 and 20,000 persons. Attendance at the free-admission Millennium was meager when compared to the Astrodome record of 66,000, achieved by another guru, Billy Graham. But it is astonishing when one realizes that in 1971 there were only six American premies, living hand-to-mouth in a two-bedroom house in Hollywood Hills.

Since then the movement has attracted graduates of the nineteen-sixties counterculture, as well as a strong element of the social protest movement, locked in step behind their standard-bearer, Rennie Davis.

It is no accident that the two states where the movement first took hold, California am) Colorado, are the playing-fields of the counter culture. There are hundreds of premies who can show you track marks on their arms. The guru attracted the walking wounded of the turn on, tune in, drop out generation, whose legacy was acid, Haight Ashbury, self-immolation in the garb of higher consciousness, and psychedelics. The movement enlisted a grab-bag of rock groupies, academic dropouts teaching in alternative universities, refugees from rural and urban communes, organic food freaks, transcendental meditationists and flower children. These were the kids who carried a yellow submarine through the streets of New York, the kids who sang "Tear Down the Walls" and put flowers in the barrels of the National Guardsmen's rifles.

As it became better known, it has also drawn defectors from the Establishment, highly trained professionals who spant their youths rising to positions of prominence -- architects, doctors, engineers, biochemists. To the alienated young people, the guru, with his claimed holiness and promises of peace, represents a valid alternative to corrupt Leaders, vested interests and official dishonesty. To the professionals, he offers a way of achieving goals that had eluded them in their professional lives: a perfect city for the architect, a more humane kind of medicine for the doctor, a key to improving human nature for the brain researcher.

Today between 44,000 and 50,000 premies belong to the guru's Divine Light Mission, which is incorporated as a tax-exempt foundation in the state of Colorado and has an estimated annual budget of $3 million. Four thousand premies live in 54 ashrams (an Indian word meaning shelter), and have taken vows of poverty, celibacy and obedience. Twenty-seven-year-old Michael Bergman who left his Job as public Information officer for the New York City Sanitation Department to join the guru, and quickly became Executive Financial Director, told me: "We're the fastest growing corporation in America. Between January and June of 1973, we grew 800 per cent. Our business practices are sound; our accounting practices are sound; our credit and collateral are sound. Dun & Bradstreet has all our financial information."

Most of the money is donated by premies, many of whom come from affluent families and are urged to give up their worldly goods when they join the movement.

The movement, which now operates in 37 countries, began in India, where it claims more than six million followers. It was founded by the present guru's father, Shri Hans Ji Maharaj, who came from a wealthy family and devoted 40 years to building up a following as a guru. When he "left his body" in 1966, Guru Maliara) ji was eight years old, but was already known as a child prodigy who Gould give powerful satsang (spiritual discourse). He was chosen over his brothers to inherit his father's mantle.

Today, Maharaj ji has been in the god business for eight years. He is not your lean and hungry guru, who lives in a cave and fasts until his rib cage shows. Nor is he the innocent, helpiess child-god, born in a manger and raised by humble parents. He is far too worldly for that, and doesn't look the part, being an oriental Humpty Dumpty as round, bland and androgynous as an egg. He speaks with brusque authority in a nasal, high-pitched, pubertal voice.

His first real media bath, a press conference at the Astroworld Hotel, was not a success. Reporters are unaccustomed to dealing with deities. They want yes and no answers, not parables. Here are some excerpts:

Q. There's a war in the Middle East; why aren't you there?

A. When a war begins, a general doesn't have to be on the spot.

Q. Why don't you sell your Rolls-Royce and buy food for the people?

A. What good would it do? I could sell it and people would still be hungry. I only have one Rolls-Royce.

Q. Are you the son of God?

A. Everybody's the son of God. You ain't the uncle or aunt of God, are you?

Q. Why do you think you can succeed when other perfect masters failed?

A. Listen, man, I'm not saying they have failed; I just say I can bring peace to this world. I'm not asking who passed and who failed.

Off stage, according to his entourage, Maharaj ji is an uncomplicated, fun-loving teen-ager, who likes to push his followers into hotel swimming pools, Ethel Kennedy style. Joe Lopez, his karate instructor security chief, told me: "I've been with Guru Maharaj ji days and days and days and days; he doesn't put on airs. Like, he'll call me over to the car and I'l1 put my head in and he'll close the electric window and catch my head in it. Another thing … he's not really fat, he's just strong. I go swimming with him, and I can tell you, he hasn't got a pauneh."

In the lobby of Houston's Warwick Hotel, on the first day of Millennium '73, two large men with Texas drawls were talking. " What's this here guru preachin' about, conservation?" the first one asked. "Naw" said the other, "it's the who am I to refuse gifts from my followers kind of thing"

The question of his emerald green Rolls-Royce, his Mercedes 600, his houses in London, New York, Los Angeles and Denver, and his private wealth and jewelry keeps coming up. "What do you expect him to do," a premie said, "travel from LA. to Houston on a donkey? Christ came on humble; well Guru Maharaj ji comes on like a king, we want him to have the best." In Houston, the best was the Astroworld's six-bedroom Celestial Suite, with its P.T. Barnum Circus room, its Tarzan Adventure room, and its Sadie Thompson room, with real mosquito netting over the bed. It goes for $2,500 a day, but the guru got a special rate. To come here from India, he had to post a bond to recover his confiscated passport while his assets are being investigated following the seizure at customs of cash and gold watches worth $65,000. More than half of it was later confiscated. "If he really was a smuggler," a premie said, "all he had to do was give each premie going to India a gold watch to put on his wrist."

The successful transplant of an Eastern guru movement to the world's most highly industrialized nation is something that fills even the holy family with wonder. I was in the Astrodame with a premie from Atlanta, Neal Hoyman, while the stage was being erected, and Bal Bhagwan ji dropped in. "Ask him for an interview," I said to Neal. "If it's proper to approach him I will," Neal said, "but remember, he is my Lord." When Bal Bhagwan ji, a thin, sallow-skinned young man with a wispy mustache, came over, I asked him why the movement had caught on here. "I'm amazed," he said, "it's mighty … but you know, in India, God is the second thing, people must fill their stomachs first. In America everyone's stomach is full but people have spiritual needs." When the word was passed that extraterrestrial creatures in U.F.O.'s would be visiting the Astrodome, it was Bal Bhagwan ji who said, "if you see any, just give them some of our literature." A space was left in the Astrodome parking lot in case any flying saucers wished to land. The reasons for the guru's American success seem to lie partly in the nature of the movement and partly in the timing of the transplant. The doctrine has about as much intellectual content as the fudge sundaes the guru dotes on. As the late Alan Watts, the all-purpose mystic and expert on Zen Buddhism, said, "The core of this doctrine is a sacred ignorance." The important thing is the experience the guru claims he can give, to change people and make them want peace. It follows, as puddles follow rain, that if everyone has this experience, the world will be at peace. God is presented as a practical experience rather than an abstraction that must be taken an faith or that is susceptible to theological demonstration. The guru promises to take doubting Thomases and make them see, hear and taste the divine. This is enormously appealing to young people who are disillusioned with ideologies and who have sought the meaning of their lives in such forms of direct experience as the protest movement and the drug culture.

When the protest movement faded, leaders and cadres, often disillusioned or burned out, began looking for something else, something that wasn't a cop-out, something that had social purpose, something that make them feel they were atoning for their society's mistakes. The worship of an Oriental child, according to a psychologist friend of mine, Jeffrey Froner, is an instinctive, unarticulated form of atonement for all the Oriental children who were killed by American soldiers in the last decade.

In any case, Rennie Davis, the guru's New Left superstar and 33 year-old Veteran of sit-ins, demonstrations and courtrooms, says, "This is the most revolutionary movement that's ever come down the pike; it's a fundamental threat to every institution rooted in ego and pride."

In the ranks of the protest movement, Rennie's conversion caused much searching of soul and gnashing of teeth. Nothing quite like this had happened since Augustine defected from Neoplatonism to Christianity. Rennie had been granted a court order excusing him from the Chicago trial where he was a defendant an charges of contempt of court so that he could be at Maharaj ji's side in Houston. Some of his co-defendants thought he had flipped out. Others thought he was an unemployed leader in search of a movement. It was as though Robespierre had turned into Saint Christopher, carrying the child-god across the stream.

But to Rennie, looking back on a decade of shattered hopes, lost battles and deadend streets, Maharaj ji represented a new start, a way of picking up and weaving together all the loose strands of the sixties. The teen-age god, immature but omniscient, was the symbol of the seventies, and perhaps of a new age.

In January, 1971, Rennie had flown to Paris to talk to the Vietcong delegation at the peace talks. On the plane he met a film crew on its way to see the guru. They talked for six hours and Rennie, at first skeptical, decided to give the movement a try. "The thing that triggered my fancy," he explained, "was that you didn't need faith; the whole thing was an experience. That's what attracted me about the New Left, the rejection of dogma and the approach by process. Guru Maharaj ji said, "Don't believe me unless you have proof." The experience brought Rennie "all the things that all the great saints refer to-it really gave me grace and moved me into a suppression of time and space." He saw the inner light. Maharaj ji appeared before him and said, "I am your Lord," just as Jesus spoke to Saint Paul on the road to Damascus.

The proof that helped convert Rennie Davis comes in a seeret ceremony that lasts from five to 15 hours, during which a group of devotees "receive knowledge" and become premies. After filling out "knowledge cards" in which, among other things, they list their financial assets in detail, they listen to a mahatma describe the mystical union between Last and West. They are told they must give themselves up cornpletely to Guru Maharaj ji, and they prostrate themselves before his photograph, for he never attends these initiations in person.

Then the room is darkened and the future premies prepare themselves for the direct experience of God through the senses. The mahatma moves about the room and demonstrates the four techniques. The first, seeing with the third eye, involves pressure an the optic nerve resulting in brilliant flaches of light. One disillusioned doctor who tried to receive knowledge said this was a parlor trick he had learned in medical school. The second technique involves hearing inner music, the third involves feeling the vibrations of the inner word, and the fourth, tasting neotar, which involves curling the tip of the tongue in the back of the throat.

Once be has received knowledge, the premie attains a state where he is "in the world but not of it." As black-belt karate expert Joe Lopez put it: "Human traits like envy and jealousy are automatically resolved and we attain the egoless state." This selflessness was a balm to Rennie Davis after a decade in the protest movement. "I've worked on many events that produced bigger crowds," he said, "but we were plagued by ego, we were freaked out, frantic, pulling at each other, waiting for the final day, and then we'd have an evaluation meeting and what would come out was how screwed up we were, how much we hated each other, and how we'd never do it again."

Such was not the case in the astrodome. The technical and organizational problems mounted, but I never saw a premie lose his temper or say an unkind word. They were cheerful, friendly, and unruffled, and seemed nourished by their faith. Their inter-office memos began: "Salutations and prostrations at his lotus feet." There was a good will and a lack of backbiting that any organisation might envy. There was no complaining about menial jobs among volunteers who put in 18-hour days. It was like the Israeli Army, where the men call the officers by their first names. It was like a wall-less, coeducational monastery.

The Divine Light Mission took the many-hued survivors of the sixties movements, put them through the spiritual assembly line, and turned them

into homogenized premie models. Many of the men are like the fifties Ivy Leaguers. Their hair is clipped; they wear conservative suits, vests and ties; they are well scrubbed and businesslike. The women favor the "American

Madonna" look, with long dresses, long straight hair, soulful eyes and fixed smiles. Astonished parents saw their freaky offspring abandon the ranks of the unwashed, go off drugs and take vows of obedience under the

influence of the Maharaj ji. Who could have guessed that these young rebels had such a capacity for reverence? About 400 parents were on hand in Houston, and some followed their children into guru worship.

The Divine Light Mission took the many-hued survivors of the sixties movements, put them through the spiritual assembly line, and turned them

into homogenized premie models. Many of the men are like the fifties Ivy Leaguers. Their hair is clipped; they wear conservative suits, vests and ties; they are well scrubbed and businesslike. The women favor the "American

Madonna" look, with long dresses, long straight hair, soulful eyes and fixed smiles. Astonished parents saw their freaky offspring abandon the ranks of the unwashed, go off drugs and take vows of obedience under the

influence of the Maharaj ji. Who could have guessed that these young rebels had such a capacity for reverence? About 400 parents were on hand in Houston, and some followed their children into guru worship.

The best way to understand the variety of people in this movement, which is the main reason it is more interesting than other guru trips, is to look at a couple of case histories, the question, in each case, would be: "What's a normal, intelligent fellow like you doing in an outfit like this?"

Tim Galloway, 35, is a California tennis pro who was once ranked seventh nationally, and who graduated from Harvard in 1960. In 1971, he heard that Guru Maharaj ji was speaking in Carmel. "I went because he was a 13-year-old from India with six million followers, and I wanted to see a saint," Galloway said. "When he said, 'I can show you. God,' I concluded he was either a fraud or a prophet. But what if it were true? I canceled a day of classes and followed him to L.A. He was answering questions in a group, and I asked him by what authority he spoke. He said, "If this knowledge fully satisfies you, you will know by what authority I gave it, and if it does not satisfy you, you will know that what I gave you was not pure water or that you were not really thirsty."

Galloway took the knowledge and felt peace. "I wasn't worried about whether I was giving a good lesson or what my girl friend thought of me," he said. "Then I spent two months meditating in India, and I returned believing beyond a reasonable doubt that Guru Maharaj ji was the lord on the planet again. He had so many opportunities to present a more convincing image, but I could never catch him pretending. The first time I saw his devotees put garlands of flowers over his head. If he'd wanted to present a convincing image, he would have thanked them and worn the garlands, but instead he brushed them aside. I could have done better myself.

"All Americans are trained to see through con artists. Harvard trained me to tear down every belief and construct and see the irrationality of it. But what to think of a kid who gicks up a can of shaving cream and starts squirting people with it? And I'm supposed to think he's the perfect master? But he's merely saying, 'If tbat puts you off, how much do you really want this knowledge?'"

Now Galloway lives in an ashram and has written a book called "The Inner Game of Tennis." He practices celibacy, which he calls Aquarian Age birth control. "Like anybody," he said, "when the urge came I looked for ways to satisfy it, but the urge just isn't coming. It's not a conscious effort; I just don't feel the need. In an ashram, there are 20 or 30 people; if they were all going to bed with each other, it would be havoc. You stop wanting to; there's a higher desire. There was that moment, but it's only a moment. Meditation is permanent; it's more blissful than orgasm."

Dr. Robert Hallowitz is a 29-year-old neurophysiolegist and a research associate at the Laboratory of Brain Evolution Behavior at the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington. A short, intense, bright-eyed man, he talks as if he were delivering a lecture. "In March, 1973, I came into contact with Guru Maharaj ji. I had a skeptical reaction; I couldn't accept him as a godhead. But with my clinical background, I saw that something was really moving the devotees in a positive direction. During a four month period I sat down and talked with nearly 100 premies. The common denominator was that they came from what we call the social dropouts. By all Establishment Standards they had been living desperate lives, unproductive and antisocial. I was impressed because I know that when encounter groups and other forms of therapy deal with this type of despair, the recovery rate is minute.

"It was visible on the faces of these premies that they were experiencing a radiant and intense peace. And it was infectious; I began experiencing the saure thing. I felt marvelous. I said, I don't

(Continued on Page 100,

(Continued from Page 96)

know who Guru Maharaj ji is, but he's giving a valid experience and I want it. Since then, I've had experience so intense as to be beyond my capacity to imagine, and if that's suggestion, it's very strong. I've come to the

point where I know there is a Supreme Being and He is one with that 15-year-old boy."

Hallowitz is convinced that the guru's teaching is consistent with recent brain research, and that meditation techniques provide a way for man to control an imperfectly designed brain away from fear and stress and toward pure thought and inner peace.

Because of his evolutionary inheritance, Hallowitz says, man is burdened with a primitive orientation towards fear and survival, which sets the tone of individual and institutional behavior, starts wars, and destroys civilizations. Scientists are already studying the physiological effects of meditation as a way out of this bind. They have found decreased heart rates and oxygen consumption, increased galvanic skin response and low-frequency alpha activity that may be correlated with states of subjective relaxation.

Hallowitz believes that receiving knowledge from the guru "involves a lowering of response to stressful situations, a heightening of capacity

for pure thought, a scaling down of body processes, libido, appetites and sleep requirements - it changes the organism's perspective of the environment; we no longer view the environment as stressful, we are no longer

draining our vitality. What I'm saying is that meditation brings about physiological transformations that have tremendous implications for our physical and emotional well-being."

Hallowitz believes that receiving knowledge from the guru "involves a lowering of response to stressful situations, a heightening of capacity

for pure thought, a scaling down of body processes, libido, appetites and sleep requirements - it changes the organism's perspective of the environment; we no longer view the environment as stressful, we are no longer

draining our vitality. What I'm saying is that meditation brings about physiological transformations that have tremendous implications for our physical and emotional well-being."

To skeptics, this attempt to connect meditation with advanced brain researeh is but one more example of the guru's flimflam. One of the most vocal skeptics is Paul Krassner, editor of The realist and in Houston to represent the scornful old guard of the protest movement. He countered the "brain overhaul" theory with the "body snatcher" theory.

The body snatcher theory holds that the guru has enticed thousands of counter-culture and New Left people away from meaningful social action and rendered them harmless. Rennie Davis is the Pied Piper who lured the radicals out to pasture. Krassner staged a debate with Davis in the Astrodome on the proposition "that Guru Maharaj ji diverts young people from social responsibility to personal escape."

In so doing, he said, the guru was acting as either a conscious or unconscious agent of the Government, which was only too glad to see tens of thousands of its critics funneled into devotional activities. Krassner said there was "collusion" between the Government and the guru. "The Hudson Institute and other brain trusts," he said, "realized the counterculture was a threat, and there was a Government plot to subvert the movement."

Rennie Davis responded good-naturedly to Krassner's attack - which included questions like "what does the perfect masturbator think when he plays with himself?" - and invoked their old camaraderie. "You gotta remember, man," he told Krassner, "it was just a few weeks ago we were in the streets together." But this seemed precisely what was sticking in Krassner's craw.

As I listened to Hallowitz, Davis, Krassner and the others, I had a vision of my own, without benefit of pressure an my optic nerve, and I realized who Guru Maharaj ji really was. He was the Wizard of Oz! When Dorothy and her friends went to the throne room of the Great Oz, each one saw something different in the center of the green marble throne. Dorothy saw an enormous bald head with no body; the Scarecrow saw a lovely winged lady; the Tin Woodman saw a terrible five-eyed and 1O limbed beast, and the Cowardly Lion saw a ball of fire.

To Rennie Davis, Guru Maharaj ji was "the Lord walking on the planet." To Houston's Bible-belt ministers, like Robert Montgomery, pastor of the Minnetex Community church, he was "an Antichrist. There is a spiritual

presence about him, but I believe it is

(Continued an Page 104)

(Continued from Page 100)

demonic." To Dr. Hallowitz, he was the agent of brain change. To Paul Krassner, he was a body snatcher. To some of the press, he was a ripoff artist, who in one night in the Celestial Suite at the Astroworld Hotel spent far

more than the average Indian's annual income. To premie parents, he was a rehabilitator of prodigal sons and daughters. To premies, he was the object of total and sincere worship. And to me, he was the perfect mirror of a

society's mediocrity. The guru, then, was whatever one wished him to be, a receptacle for our aspirations and fantasies. As amorphous and elementary as a lump of dough waiting to be kneaded and baked, he was the perfect

mass leader for a generation grown wary of charisma. But what is the Divine Light Mission, with its tens of thousands of members and millions of dollars? It is a textbook example of mass-movement psychology, as described in

Eric Hoffer's classic book, "The True Believer." The Divine Light Mission is a haven for a new kind of true believer, the middle-class misfit.  It

satisfies his passsion for self-renunciation, for getting rid of an unwanted self, it offers a substitute for individual hope and a vehicle for change. It must not be judged on its doctrine, but on its corporate ability to

absorb the frustrated. The effectiveness of the doctrine does not come from its meaning but from its certitude. The guru can speak nonsense as long as he presents it as the one and only truth. Like members of other mass

movements, the premies are tireless proselytizers, who strengthen their own faith by converting others. They believe their view will eventually be adopted throughout the world, not by force or conquest, but by superlor

marketing of their product.

It

satisfies his passsion for self-renunciation, for getting rid of an unwanted self, it offers a substitute for individual hope and a vehicle for change. It must not be judged on its doctrine, but on its corporate ability to

absorb the frustrated. The effectiveness of the doctrine does not come from its meaning but from its certitude. The guru can speak nonsense as long as he presents it as the one and only truth. Like members of other mass

movements, the premies are tireless proselytizers, who strengthen their own faith by converting others. They believe their view will eventually be adopted throughout the world, not by force or conquest, but by superlor

marketing of their product.

Renting the Houston Astrodome was part of this marketing campaign. The show went on relentlessly. On the third and final day, Larry Bernstein, a prize-winning, 41-year-old architect who left a $50,000-a-year job to join the guru, described the Divine City the movement plans to build, perhaps in Virginia's Blue Ridge mountains, it will run on solar energy, and the basic building unit will be a hexagonal plastic shell. Gas-propelled vehicles will be banned, and public transportation will consist of computerized monoralls and duorails with detachable cars that take you to your building elevator. Simple medical diagnosis will be obtainable by telephone; goods will arrive in your apartment by pneumatic tube; birth control will be by pineal gland cutoff, and teaching machines will teach you four languages in five weeks by tuning in an your alpha waves. Every need has been foreseen, from a place to make movies called Holywood to a tooth brush with toothpaste in the handle.

That evening, Maharaj ji gave his final talk, using his favorite image of the automobile (relating to the culture, a premie explained, as Christ talked about fishermen's nets): "This life is a huge car," he said, "and inside there's a big engine and a carburetor which runs a line called a fuel line in saure cases there's a filter and if there's any dirt in that fuel it'll filter it right out so there won't be any disturbance in the operation of the car. In our lives the filter is called knowledge. There are so many particles come in an our fuel line from our feelings and desires. …"

"You know," a premies father said, "he speaks pretty good English."

"You know," the premie's mother said, "he made an impression on me; when he said everyone should be quiet, people were respectful."

The Divine Light Mission's president, Bob Mishler, bowed before the guru's throne and presented him with a gold swan. The premies threw up their arms and shouted, like 20,000 cheerleaders: 'Bolie Shri Satgurudev Maharaj ji Ki Jai [All praise and honor to the perfect living master]." The guru and the holy family vanished backstage. The Blue Aquarian musicians packed their instrumernts. "The most significant event in the history of humanity" was over.

Nothing had happened. The earth had not moved. There had been no miracles. Maharaj ji had blundered in a peculiarly American way-he could not live up to his advertising.

But the faith of his followers was not shaken. They were convinced that mysterious unseen forces had been at work in the Astrodome, doing his bidding, The message "Please leave the Astrodome immediately" flashed an the scoreboard, and the tbousands of premies obediently filed out.

Volunteers began to dismantle the stage and roll up the red carpeting that covered the Astroturf. By contract, the Divine Light Mission had 8 hours to clear the stadium, so that the Astrodome people would have time to get lt ready for the Sunday Football game between the Cleveland Browns and the Houston Oilers. By noon, the Astrodome's "Earthmen," dressed in orange, were vacuuming the field, and soon 37,230 football fans watched the Browns beat the Oilers, 23 to l3.

Copyright The New York Times

Originally published December 9, 1973