Part Two - The Wrong Approach: Looking To The Di-Verse.

5 - Where To Look?

We have made the starting point of our enquiry the question, "How can can we escape Unpeace and find Peace?" where we defined 'Peace' and 'Unpeace' in the most general way possible. 'Unpeace' can range from the most terrible suffering to mere irritational discomfort; it is that which prompts us, eagerly or reluctantly, to perform actions. It is a state of disharmony or unequilibrium, which we are dissatisfied with and which, consciously or unconsciously, we struggle to transcend.

Of course, it is often held that much that is beautiful and creative stems from such tension, suffering and disharmony, a case such as Van Gogh being cited for support. While the opposite viewpoint can however be equally well held (for instance Wordsworth, Mozart and Bach all created from tranquillity rather than harsh conflict), the point is that even if an artist produces a great work for mankind's posterity out of his suffering and Unpeace, surely he himself is still trying to escape his suffering? Anyway, we can always avoid the problem by defining Unpeace as that which we want to avoid!

In this sense, the question "how best to escape Unpeace?" is very basic and fundamental; more so even than the usual philosophical starting point such as "Who am I?" or "What is the nature of this world?" After all, we will only be led to ask these kinds of questions by the realization that our present situation and understanding are insufficient for obtaining Peace. An example of this is the case of Descartes, the French philosopher mentioned in the last chapter. He lived in a world of obvious Unpeace; in particular there was almost continuous religious conflict between the Catholics and the Huguenots. He was caught up in the Thirty Years War (1619-1649), fighting first in Bavaria and later in the siege of La Rochelle. There was also conflict in the philosophical field between the advocates of Aristotle's world-view and those who supported the new theories of Galileo and others. It was this lack of security and certainty all round which led Descartes to his fervent search for unshakable knowledge, and which resulted in his famous 'cogito': "I think, therefore I am." Out of this certainty of his own existence, Descartes attempted to build a system of philosophy which was impregnable.

The point we are making is that the need to build up a philosophy or to understand the world is generated by Unpeace. Indeed, not just philosophy, but all the 'noble' activities of man, such as science, medicine, art, helping and loving others, in that they are activities are as much attempts to answer the question of Unpeace as are war, hatred, cruelty etc

Like Descartes, we are basing our enquiry on the universal fact that must be true. Rather than choose the fact of our existence to build on, we are choosing the fact of our experiencing Unpeace. We might even twist Descartes's 'cogito', and in place "I think, therefore I am" proffer, "I suffer, therefore I act."

Most of Part One was concerned with showing that the key word in connection with Unpeace is difference. We live in a world of difference, where everything is separate, changing and indeed different. The transience and changeability of all objects and situations means that nothing is or even can be certain, except the fact of change itself; and this causes continual tension and conflict on all levels (biological, psychological, social and intellectual). This in turn means that we have to be always changing and adapting to new situations, always evolving, never being but always becoming, or, as we expressed it in the first chapter, always being born.

For animals, and indeed for all sentient creatures other than man, this process is only on the physical level; but for man, this process is also in operation at levels distinct from the physical. In Chapter One we attributed this to a duality of natures in man - animal and human. But although this is a very useful way of looking at man, it is only an analogy, and we would be in a false position if we were to argue from it.

Instead, we will turn to the basic duality dealt with in the last chapter - that of mind and matter, or the private and public worlds. But rather than examine them philosophically, as we did in the last chapter, we will do so now practically. For this book is essentially practical - we are dealing with the practical problem of suffering and misery, fear and hate, bewilderment and confusion. Philosophy and intellectual word-pushing are only useful for our purpose in as much as they enable us to see clearly where the practical solution lies and how it might be obtained.

The philosophies mentioned as having some bearing on the mind-matter duality are all very well, but do they in themselves offer a practical solution? Of course, this question presupposes that it is possible to understand the philosophies in the first place. Some philosophy, particularly that of the idealists, can be so abstruse that when someone wrote a book entitled, "The Secret of Hegel's Philosophy," a reviewer observed that the author had kept the secret very well! 1

In this enquiry we are not so much interested in the mind-or-matter controversy as such, but more in the fact that in everyday life we in practice experience these two worlds, the public and the private (or matter and mind), whatever the philosophers may say.

Now our behaviour, our answering of the question how to avoid Unpeace, will basically depend upon which class of object (public or private) we look to most. For everything we experience must fit into one of these two categories - either it is private and cannot be experienced by anyone other than the person concerned, or it is public and can be experienced by anyone (in principle). And granted that it is our experience that we are in Unpeace, and that this is due to our experiencing a world of difference, then the question becomes whether we look primarily to the public or the private world to find Peace.

The Three Monks

To illustrate this point, we can look at a short story from the Chinese work 'The Gateless Gate' written in 1228.

Once, two Zen Buddhist monks were arguing about a flag blowing in the wind. The first monk said, "The flag is moving." The second monk said, "The wind is moving." Just then a third monk happened to be passing by. He told them, "Not the wind, not the flag; mind is moving."2

In other words, the first monk states his experience - that he sees a flag moving. The second monk looks for the explanation in the public world, while the third monk looks for the explanation in the private world. What exactly the third monk might mean by "mind is moving" we will not enquire; the important thing is that he explains a public event (the moving flag) in terms of his private world, while the second monk pursues the more obvious course of explaining the public event of the moving flag in terms of another public event or object (the wind).

Of course, if the first monk were to have observed a private event (such as pain), then the third monk's attitude is more comprehensible. We can retell the above story with the monks now discussing a subjective event, like this: First monk (looking at his cut hand): "This wound is causing me pain."

Second monk: "The knife that cut your hand is the cause of the pain."

Third monk: "Not the wound, not the knife; your experiencing (ie your consciousness) is the cause of the pain."

Although we agree with the second monk, that the knife is in some way responsible for the pain, nevertheless the third monk is also correct. If it were not for the first monk experiencing the pain, there would be no pain - this is what we mean by a 'private object'. If this first monk were unconscious, then certainly blood would still flow from the wound, neural impulses would go up the nervous system, electrochemical events would take place in the brain, but there would be no pain.

Whether to basically follow the second or third monk is tantamount to the question: what is more important - the way we look at things (the third monk's viewpoint) or the things themselves (the second monk's viewpoint)? Since the first monk has the role of mutual observer, we can say that it was he who was responsible for Part One of this book. He observes mankind (himself included) to be in Unpeace, notices that our behaviour is motivated (consciously or unconsciously) by the compulsion to end this Unpeace, and he observes that the root cause of this Unpeace is the essential difference we see everywhere. So far, so good. But now the second and third monks come onto the scene. We will take it for granted that they both accept the first monk's formulation of the problem; their solutions, however, will be very different and will lead to divergent styles of behaviour. Consider an example:

Suppose the first monk is fat, and as he walks down the street someone yells, "You fat slob:" A few minutes later someone else shouts, "You gross pig!" and not unnaturally, he gets angry. Now the question is, what is the cause of his anger? The second monk would tell him that he got angry because people were being rude to him. But the third monk would tell him that his anger was due to his state of mind, the way he was looking at things; if he were being carried down the road unconscious, then he would not hear any of the remarks and would not be angry; alternatively if he were in a happy mood, he might laugh off the insult, but if he were in a bad mood, then the insults would make him very angry.

Now we are all in a position similar to the first monk of being in Unpeace; we sometimes find ourselves frightened, sometimes angry; sometimes we suffer physical pain, sometimes mental pain. But do we follow the second or the third monk? In practice, the vast majority of us follow the second monk; we act as if it were public object and events which are the cause of our content or discontent. If we are bored, we watch television; if we are depressed, we have a drink; if we are unhappy, we watch a funny film; if we cannot sleep, we take pills. Advertisements tell us that this furniture polish takes the drudgery out of housework, that washing powder takes the dreariness out of washing. Do we want the 'real thing'? Then drink Coca Cola. Do we want pleasure? Then smoke such-and-such cigarettes. If someone calls us a fat slob, then we shake our fist at him.

But if we follow the third monk, we shake our fist at our own mind. And if we are able to be somehow in that state of mind where the world seems a good place, where we are looking at it through 'rose-coloured spectacles', then public objects (such as personal insult) will have little or no effect on us.

One advantage of taking notice of the third monk comes about because we have only a limited control over our environment. Suppose I am bored; then if I follow the second monk, I turn on the television. But what if the television station is not broadcasting at that time of day? Now, if I follow the third monk, I will not turn to the TV (ie a public object) to eradicate my boredom, but I will look to myself (the private world) and try to be in a state of mind where boredom does not exist. If I can do this successfully, then I am in a far superior position to the followers of the second monk, because I always carry myself around with me, whereas there are obviously times when I am not with the TV!

Similarly, we can take the cause of the insulted fat first monk. If he took offence at the first insult ("You fat slob!"), then he would do one of two things: if he follows the second monk, he would verbally (or even physically) attack the insulter, whom we shall assume he overwhelmed, so that the insulter promises that the monk is not fat, certainly not a slob, and is in fact quite slim and well-looking. If, on the other hand, the first monk follows the third monk, he would ignore the insult and would examine his own mind. Either by reasoning or by some psycho-spiritual technique, he would attain that state of mind whereby he was genuinely unconcerned at what anyone called him. The insult would wash off him like water off a duck's back.

Up to this point, both approaches seem equivalent in having led to the same result. But now consider the second insult ("You gross pig!") shouted a few minutes later. To become peaceful, the follower of the second monk will have to go through an identical process with the second insulter as he did with the first insulter. But the follower of the third monk will already be peaceful. Why? Because he is carrying around with him his peaceful state of mind which he generated after the first insult.

If he were a learned monk he might quote Milton:

"The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven." 3

(though not, of course, if he were a 13th century Chinese monk). It is also unlikely that he would know about the United Nations charter which says, amongst other things, "War begins in the mind of men, and it is in the mind of man that the defences of peace must be constructed." (Though there is no doubt that he would agree with it were he to have known of it.) So we can see that the difference between the viewpoints of the second and third monks in fact leads to a totally different type of behaviour in the same situation. And it appears that the third monk's behaviour is eminently more reasonable and successful in avoiding Unpeace. Why, then, do the vast majority of us in most situations follow the second monk?

The reason is very simple; we do not know how to follow the third monk. How can we generate from within ourselves a state of mind which enables us to look at everything peacefully and in terms of harmony and love? How can we automatically be in a state of consciousness such that all, difference is transcended, so that a bayonet in our stomach is a trivial matter, and even death is superficial? The failure to find an answer to these questions forces us to dismiss the third monk's attitude as far as practical every-day living is concerned, and to act like the second monk. The hallmark of the second monk's attitude is, as we have seen, that he thinks it important to control and manipulate his environment of public objects. He takes this viewpoint either because he thinks his surroundings are ultimately the cause of his Unpeace, or because the third monk's attitude seems impractical, or both.

To tie a philosophical label around the second monk is difficult, for he does not really fit into any existing category. He may well be a materialist, but he could equally well be an idealist, since we have not tapped his belief on the actual 'reality' or otherwise of the public world; he merely acts as if the public world were more fundamental and the cause of his Unpeace. The story is told of how Bishop Berkeley (who held an extreme form of idealism) went to visit Dean Swift. Swift, however, kept Berkeley standing on the doorstep, on the grounds that if his philosophical views were correct and the closed door only existed in his mind, then he would have no trouble in entering! 4 In other words, in spite of his philosophy, Berkeley was forced to act as the second monk.

In this book, we will call the second monk an 'externalist' and his way of behaviour externalism. We define an external object or event to be an object or event which belonged to the world of difference, and vice versa; that is, an object or event pertaining to the world of difference is defined as being external.

Summary

We began the chapter by summarising Part One - that we act because of the Unpeace we find ourselves in, and which is essentially due to the world being one of difference. Given this situation, our behaviour can be broadly divided into two categories, as that which results from laying emphasis on either the public world, or the private world. The former behaviour we call 'externalism'. While we may see the advantage of the latter category of behaviour, the difficulties involved in carrying it out means that most of us are externalists in practice.

- Externalism

The externalist thinks that the most important thing for him to do is to have control over his environment, since he believes it is his external surroundings which largely control his happiness and well-being.

Now of course there are many ways to try and control the environment. Basically they can be divided into two: what we can call 'indirect externalism' and 'direct externalism'. Indirect externalism is, as its name implies, an attempt to control the external world indirectly. All primitive peoples, and not-so-primitive people as well, rely largely on indirect externalism. It is evident in magic, miracles and all appeals to some supernatural agency for help in rearranging the external world somehow. It sometimes has the awe-inspiring name 'thaumaturgy', and there has been much study into its practice.1 Not only do we see indirect externalism in the animistic beliefs, prayers and sacrifices of the so-called primitive peoples, but also in the exorcism of ghosts, the blessing of ships and the claims to miraculous healing at Lourdes and Fatima in the present day. We can also include possibly the phenomenon of PK (psycho-kinesis), the ability to manipulate external objects by thought power. (PK will be discussed briefly in Chapter 7). Indirect externalism was rife in the Middle Ages, particularly in regard to witchcraft and the miracles performed on account of religious relics. Nowadays many devout Roman Catholics still pray to the various saints for help and protection in everyday life, such as to Saint Anthony of Padua for finding lost things.

Direct externalism is, on the contrary, an attempt to control the environment directly. Of course the dividing line between direct and indirect externalism is very vague, but nevertheless it is a useful classification.

We can further divide direct-externalism itself into two broad categories - those expressions of it which rely mostly on physical force and conquest of peoples, and those which tend to rely more on the intellectual and reasoning powers. All great empires tend to be products of the former category, and include the Macedonian empire of the 4th century BC, the Roman empire (certainly in its later stages), the Arab empire of the 7th and 8th centuries, the Mongol conquests of the 13th century and the Spanish and English colonisations of the 16th century. The common factor in these conquests is not only a desire to control the external world, but a desire to do so directly through physical force.

In this chapter, however, we will be concerned with the latter category of direct-externalism, ie that of controlling the external world by acquiring knowledge of it through the intellect and discursive thought.

Science

The most obvious example of this for us is the rise of science in Europe over the past four hundred years, and the resulting technological and world-wide materialistic developments it has engendered.

That the growth of science is essentially externalistic is strikingly illustrated by a remark by one of the founders of modern science, Galileo: "The conclusions of natural science are true and necessary, and the judgement of man has nothing to do with them." 2 The second monk could not have put it better himself. Since the direct externalist believes that what happens 'out there' in the external world is important, and is not influenced by 'the judgement of man', then it becomes necessary to understand and to obtain knowledge of the external world and thus hopefully to control or master it. Modern science has achieved this mastery to an astonishing degree, its success being celebrated in such phrases as "the conquest of Space" with regard to the space projects; in fact, the aim of science as a whole is frequently expressed as the "conquest of Nature". This of course explains why science is the ultimate authority for dedicated direct-externalists, because they believe it is in the 'conquest' of their surroundings that they will find true happiness, total satisfaction and that Peace which we are all looking for.

Science is now the new religion; Genesis is not in it with a school text-book on chemistry, and we even rely on scientific text-books for such personal crafts as rearing children or achieving a happily married life. In this section we will take a brief look at science in the West over the past four hundred years, but before we proceed, it must be noted that we are not making any cut-and-dried propositions, such as "western culture is external or materialist" or "eastern philosophy is spiritual and mystic", Although western culture undoubtedly is externalistically orientated it has strong elements of non-externalism, notably the philosophy of the Christian Church. And while it is also true that eastern philosophy is largely non-materialistic, the East has produced materialistic schools of thought, notably the 'Nastikas' of Krishna's time and later the 'Charvakas', who anticipated and outdid the direct-externalists and materialists of the modern world in their thinking and behaviour, Also Buddhist mysticism, commonly supposed to be absolutely idealistic is linked with the theory of knowledge that would satisfy the most die-hard western externalists; and what is usually perplexing to the western observer is that the discipline of Hatha Yoga, for instance, while repudiating the external human body, is largely concerned with the preservation of physical health.3 As regards modern times, the person who thinks the East is totally spiritual should visit downtown Tokyo or almost any large, industrial Asian city; and the person who thinks that the West is totally materialistic should visit any of the innumerable spiritual, or even 'hippy' communities which have sprung up recently in the industrial West.

With this preamble, let us look at that expression of externalism in the West we call 'science' and see what it has contributed to the establishment of Peace.

We will start with 17th century, which is probably the most important, most eventful, and changeful single century we know of (excepting our own 20th century). Consider that was achieved in those hundred years. There was a great advance in the instruments for measuring and analysing the world: the compound microscope was invented in 1590, the telescope in 108 and a little later the thermometer, barometer and airpump; and clocks, while not new, were enormously improved in that time. In the field of medicine, Harvey published his discovery of the circulation of blood in 128 and Leeuwenhoek discovered protozoa (one-celled organisms), spermatazoa and even bacteria. In mathematics, the outstanding achievements were Napier's inventions of logarithms in 1614, Descartes's invention of co-ordinate geometry and the invention of calculus made simultaneously by Newton and Leibniz. And of course the most staggering achievements were in the fields of astronomy and dynamics: Copernicus put forward the revolutionary theory that the earth orbits the sun (although he belonged to the 16th century, his theory was only well-known in the 17th); Kepler simplified this theory with his famous laws of planetary motion put forward in 1609 and 1619, which confounded the 'obvious' belief that the planets were perfect bodies moving in perfect figures (ie circles - Kepler showed they moved in ellipses); Galileo founded dynamics, discovering and inventing acceleration, the law of inertia and the 'parallelogram law', and in astronomy he discovered Jupiter's moons, the phases of Venus (thus proving the Copernican theory) and that the milky way was composed of stars. In the year that Galileo died (1642) Newton was born. The achievements of Newton were very great; from his three laws of motion, every mechanical phenomenon could be explained until the end of the 19th century.

"Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night.

God said 'Let Newton be', and all was light." (Pope)

The universe became lifeless and inert, moving mechanically and inexorably by its own laws. Maybe God was needed to give the whole thing an initial kick to get it going, but after that he was an unneeded hypothesis. In fact, since it was not clear whether the world had a beginning in time, God's existence was altogether doubtful.

This incredible leap in the understanding and knowledge of our universe completely changed men's outlook. In 1600 the mental outlook was totally medieval, except for a very few outstanding individuals. By 1700, the mental outlook of educated men was completely modern. In Shakespeare's time (1600) comets were omens from the gods; after Newton's 'Principia' in 1687, comets became docile pieces of matter, as obedient to the law of gravitation as the planets were. In 1600, there were witchcraft trials; by 1700 they were impossible, for law and reason reigned so supreme that magic and sorcery were unthinkable.4

Thus we see that we have, by 1700, a thorough direct-externalist view of things, which began in the success of understanding and controlling the environment and which manifested itself in the whole spectrum of man's activities. Take architecture; in 1600 the style was Elizabethan and flamboyant, but by 1700 it was 'elegant' and dominated by classical proportions. In the field of literature, we have in 1600 such writers as Donne and Shakespeare, who were rich, irregular and exciting; by 1700 we have the dry and controlled intellectual wit of Pope and Dryden. In 1600 there were countless religious wars between varying sects, but by 1700 they had ceased, and we even had the Toleration Act allowing Roman Catholics into Great Britain. It was as if there were a great need for control, classification and security in all activities; the flamboyance and irregularity of 1600 were not to be entertained in 1700. We see this even in politics: in 1600 the politics were very unstable, but it was exciting, with Roundheads, Cavaliers and the Civil War. But by 1700 the government was very stable and dull; the Whigs and Tories were hardly differentiable, and the monarchy in the persons of William III or George I was eminently austere and reeked of security.

But how did the success of science affect the common people? What practical effect did it have on them? Well, life was hardly rosy in the early 18th century. In 1715 it was noted that of the 1,200 babies born every year in the parish of Saint Martin-in-the-Fields, 900 died in infancy; infant mortality in the work-houses was 38 per cent. Money was frequently stolen, accounts falsified and paupers starved and murdered. It was an age when hygiene was atrocious, violence was taken for granted; hanging, drawing and quartering was a popular and frequent public spectacle, and men "lived cheek by jowl with death and disease in their most gamesome forms" as a famous historian puts it.5 He then goes on to say that this state of affairs was good! Most historians agree that life in the early 18th century was comparatively easy in comparison with before and after. For afterwards, later in the 18th century, we have the beginning of the Industrial Revolution; this was when the great scientific advances in knowledge percolated down to become a technology which affected everybody. There is no need to catalogue the inhumanity and oppression, the slums and the misery it caused. It was a direct result of that type of behaviour we have classified as direct-externalism. For man's greed is always with us, but it was only in the die-hard direct-externalism of the 'new' science that man's inhumanity to men found such a powerful weapon for magnifying his selfishness.

That is all very well, the reader may say, but that was in the past; what about the present day? Well, we pay homage to science today for two reasons: one is the collection of devices it has produced which make life easier (or the destruction of life more efficient), and secondly we hold it in awe for the magical effect it produces. Let us take the last point first, dealt with by Dr Ravetz:

"When the layman (child or adult) sees a demonstration of some astonishing effect, can he imagine the human endeavour and intricate technical work which led to its creation? No: it is the effect itself which captures the imagination, and produces wonder and delight: this is natural magic. Of course, the audience of the 'wonders of science' is told that these achievements are simply the application of the laws of Nature, and that the creator of the effect is in no sense a magician. But since the audience cannot understand the laws of Nature that are relevant to the production of the effect, it is strange and wonderful (until it becomes a commonplace part of the environment) and so differs little from natural magic of the old sort. We can see the strength of this attitude from the great popularity of projects that are politely described as science but which are clearly recognisable as merely pure natural magic; the manned exploration of space is the best example." 6

But although the 'magic' of science is always increasing, the moral status of science has recently gone into decline. For several generations, up to the very recent past, 'science' was conceived of as a quest by dedicated individuals working in purity and innocence to increase knowledge and to discover the true laws of nature. It was as moral innocence that a group of physicists urged the U.S. government to produce an atomic bomb, but with the nuclear holocausts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki science lost its innocence forever. At the present day science is at best looked upon as a vulgar and commercial tool of industry, and at worst as an inhuman discipline of military interests, producing wicked devices of unparallelled savageness (eg nuclear, chemical and biological weapons). And since the study of ecology became prominent, we are learning of ever new and more subtle ways in which scientific knowledge and technology are poisoning the environment and ourselves. The terrible thing is that hardly any field of scientific research can claim itself to be blameless, since advanced scientific discoveries are so complex that they often call upon a very broad spectrum of research results, and the most innocent scientific 'fact' can tomorrow be used to help construct a device of powerful destruction.

There is also of course the horrific possibilities of mass control by a government which scientific knowledge and technology has made feasible. These range from genetic engineering to complex bugging systems and communication control, which have been gruesomely predicted and described in George Orwell's "1984" and Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World".

Thus a feeling is growing that science has prostituted itself; indeed, one scientist thinks that science's crime is not mere prostitution, but simony, which used to be defined as the perversion of magic to other ends than the Greater Glory of God. He writes:

"There is a sin which consists of using the magic of modern automatisation to further personal profit or let lose the apocalyptic terrors of nuclear warfare. If this sin is to have a name, let it be Simony or Sorcery." 7

But really the tarnishing of science goes much deeper than that. As Dr Ravetz says: "Western science has had a long period of happy adolescence; developing adult powers while enjoying children's irresponsibility. Combined with ideals of 'national enlightenment' in the 18th century and industrial development in the 19th century, it seemed for some generations to deliver the good things that magic and religion only promised." 8

But that has finished now. Not only do we see scientific knowledge being responsible for ingenious horrors of destruction and pain, but we also see it making an artificial environment producing misery and pain in a much less obvious fashion, and for which it must accept its 'adult' responsibility.

In part one, we had a rundown of some of the main sufferings which affect human beings. Some have been increased as a result of scientific knowledge (eg the ability for wholesale slaughter, or the strain of urban society); some have been lessened (eg disease and physical discomfort). No one would deny that the miracles of science have in many fields brought unprecedented comfort and ease, but the modern scientific and technological age with its vast range of material panaceas has not eradicated suffering and established Peace. On the contrary, many people nowadays think that the stress and strain of modern living more than offset the increase in physical comfort, and lead to a net increase in the big Unpeace of the world.

So although we do not doubt the obvious power of scientific knowledge, what we claim here and hope to have shown on a purely historical and practical basis, is that science and scientific technology have not brought about Peace - indeed, it can be said that in the overall picture that they have not, on average, even lessened Unpeace.

Summary

In this chapter we distinguished between indirect-externalism and direct-externalism, and dealt primarily with the latter in its modern-day guise of 'science'. We dealt with the rise of science in the 17th century and its effect in the 18th century, and with the basic effects of modern science today, showing on a practical basis that this aspect of direct-externalism has done little, if anything, to lessen Unpeace as a whole.

7 - Discursive Thought

In the last chapter we showed that the outward going effort and involvement in the world which is the hallmark of the direct-externalist is one ingredient of modern science. But direct-externalism by itself does not lead to science (we quoted the example of expansionist empires); another ingredient is needed, and we mentioned that as being intellect or discursive thought.

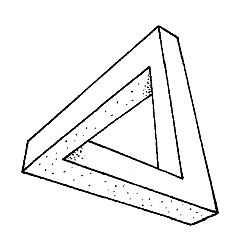

Now the word 'discursive' means literally 'running into two,' and so discursive thought can be defined as that thinking which is 'running into duality'.

In fact, it can be held that all thinking is really discursive, since to think clearly we have to clothe our thoughts in words, whether we speak them or not. To think without verbalising is impossible; anyone can verify this with five seconds of introspection. And since words are like labels we use to classify, distinguish and communicate various aspects of experience, they very definitely belong to the world of difference and duality. Thus all thought, being verbalised mental activity, also belongs to difference and duality and is thus by definition 'discursive'. (Although this word 'discursive' is normally only applied to thinking or reasoning, we will use it to describe any activity involved with duality or difference, which is its literal meaning.) The mental faculty with which we think we will term the 'intellect, which is the common usage it has nowadays, though it used to mean rather the opposite at one time.

In this chapter we will look at discursive thought, first in its main form as reasoning, and then as it is applied to understand the world in both science and metaphysics. However, before we proceed, we can note that since discursive thought is thinking through and about duality and difference, then all it can ever hope to do is to rearrange difference. But in Part One we saw that our Unpeace was due to our living in the world of difference; and thus it follows that Peace can never be achieved through merely rearranging our external environment of difference - for we will still be faced with difference. Thus discursive thought and the intellect are unfitted for the task of obtaining Peace. This is really the heart of this chapter; what follows is an attempt to support this in various ways.

Reasoning

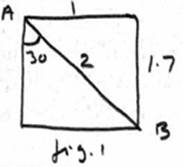

Reasoning is that type of thinking which produces reasons for coming to a certain conclusion. Take an example: suppose I want to move my desk out of the room, and I don't know whether it will fit through the doorway. Now there are several ways I can think about the problem. I can learn from someone that it will not, in fact, go through the doorway. I can remember from a previous occasion that it did not fit, or maybe on intuition or in day-dreaming I just accept the fact that it will not fit. Fourthly, I can suppose as a matter of hypothesis that it will not fit. Now all these ways of thinking (learning, remembering, intuition, day-dreaming, supposing etc) have in common the fact that I do not produce reasons as evidence for my conclusion. But if my thinking about the problem takes the form of reasoning, then my thoughts will be something like this: "the desk will not fit through the doorway. The reasons are i) the desk is four foot wide, ii) the doorway is three and a half foot wide." In other words, my conclusion rests upon reasons.

We can observe to start with that reasoning, being discursive thought, is concerned totally with difference. In the process of reasoned thinking the mind works from point to point; it jumps through a series of different stages. Furthermore, the situations and problems to which reasoning is most often applied are those of difference, where something has to be related in some way to something else. So in a world where the most basic quality is difference, reasoning is obviously very useful. And because we all see difference everywhere, everybody uses reasoning to some extent.

But the direct-externalists, for whom the world of difference is fundamental, will (if he is intellectual) be preeminently concerned with reasoning. It will become, not just one tool amongst many, but the most useful and important tool for understanding a cosmos riddled with difference. And since of course an understanding of Nature is a prerequisite to 'conquering' her, then for the intellectual direct-externalist, reason reigns supreme, not merely a queen but a god, and an entire age is named after it. It follows that if reasoning is held in such estimation, then it is very important that it should be as refined and polished as possible - and this is the purpose of logic.

i) Logic

The study of logic has become incredibly complex and mind-twisting, such that any simple statement about it is invariably misleading. Nevertheless, we will continue undaunted and pick our way through one of the densest jungles man's intellect has grown.

A working definition of 'logic' for the layman is 'the science of good reasons', or that discipline which attempts to distinguish bad reasoning from good reasoning. It attempts to formulate rules which can tell us whether the reasons we have given are 'good' reasons for inferring the conclusion we wish to establish. It is important for the intellectual, as we have pointed out, to make his reasoning correct and effective, and so logic is a very necessary study for him.

The abstruseness of logic is to some extent due to the fact that it crosses back on itself, being reasoning about reasoning (note that then the study of logic is reasoning about reasoning about reasoning).

Obviously logic, or the polishing of reason, has different connotations according to which angle we view the process of reasoning from. For instance the psychologist views logic as a study of the reasoning process as manifested by individuals, whereas from a sociological viewpoint it might mean the rules for reasoning as laid down by custom (as John Dewey thought1). Alternatively, logic can be viewed as a sort of craft, or almost as an art, which an astute thinker can use to his benefit; and a fourth interpretation is to exclude all actual human thinking from logic, and to think of logic as merely dealing with the relationships between propositions. In the latter, the propositions themselves are immaterial; it is the relationships between them which are studied. This form of logic (called Symbolic Logic) has been very important in mathematics and philosophy and will be briefly discussed later in this chapter.

But first we will look at a feature common to all types of traditional logic (including Symbolic Logic), and that is their basic duality of 'is' or 'is not'. The reader will remember that in chapter 4 we discussed briefly this basic duality, showing that since we see ourselves in a world of difference we are governed by the duality that either something is, or it is not. Either I am six foot or I am not; either it is raining, or it is not;.

Now logic, since it deals with the world as we see it (or rather deals with the reasoning about the world) is forced to accept this duality. Even forms of modern symbolic logic, which claim not to deal exclusively with the world, still have to accept this very fundamental duality in the sense that even statements about relationships between meaningless propositions have to be either true or false. They cannot be both true and false, nor can they be neither true nor false.

But due to the findings of modern science, it seems that this basic 'law' is not always correct. For instance, Albert Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity (discussed in Chapter 13) says that I can be both six foot tall and five foot tall from different viewpoints. This is quite complicated to go into here without the necessary preliminary grounding, but the discrepancy does exist, and has created havoc in philosophical circles. For a more detailed explanation the reader must wait until Chapter 13.

A clearer instance of the possible breakdown of the 'law of the excluded middle' lies in quantum mechanics, the physics of the very small (eg atoms). Since the 17th century, science has performed many experiments which show clearly that light is composed of waves. However, at the beginning of the 20th century some experiments were performed which showed that light consists of particles (called 'photons'). The amazing thing is, that this latest discovery did not invalidate the earlier findings. In other words, light can be considered as a wave and as particles. Yet a wave and a particle are completely different. For instance, a wave will bend round an obstacle (compare a water-wave bending round a post) while a particle will bounce off (like a ball hitting a post). This perplexing state of affairs was soon extended to matter. In 1925 Schrodinger demonstrated that particles of matter could be considered as waves, while at the same time Heisenberg shoved that particles of matter could be considered as particles! Within a short time, Dirac showed that the two descriptions were two views of the same thing. One view was based on the concept of differences in time (change) while the other was based on the concept of differences in space (separation).

Thus we get the situation that, for instance, the electron both is and is not a particle. This is valid from our human point of view, but logically it is meaningless. In other words, it seems that as science pushes up against the limits of the universe, the most fundamental tenet of our commonsense logic fails us. To the scientist, however, there is no real confusion. He just says that his equations and formulae describe the electron and that is that; if the non-scientist wishes to interpret what the equations mean, then that is up to him. But nevertheless, the admission that the equations of quantum mechanics cannot be interpreted in terms of classical mechanics or 'common-sense' logic, shows that when it comes to the crunch, one very fundamental duality seems to vanish. In fact, this is not only true in quantum mechanics; can the rigidity of the law of the excluded middle, and of logic in general, be applied to art, to beauty, or to love?

Anyway, we will return now from the crazy logic of the atom to the ordinary everyday logic we are familiar with. We will now look briefly at the two traditional divisions of logic - deduction and induction.

ii) Deduction

Deductive logic is concerned with the rules for arguing from the general to the particular. For instance, if I make two assumptions (technically called 'premises') such as "All Englishmen are human beings" and "All human beings are mortal." then by the rules of deductive logic, I can infer that, "All Englishmen are mortal." In other words, from general statement (concerning all human beings) I have inferred some information in a particular statement (concerning just some human beings, ie Englishmen). It is very important to note that since logic is only concerned with the rules of reasoning, it can say nothing about the truth or otherwise of the premises, and thus nothing about the truth or otherwise of the conclusion. It can only say that if the premises are true and if the deduction is sound, then the conclusion must be true.

For instance, consider the following deductive argument: "All Englishmen are human beings. All human beings are cucumbers. Thus it follows that all Englishmen are cucumbers." Now the deduction is completely sound, but one of the premises ("All Englishmen are cucumbers.") is obviously false. In other words, deduction alone is powerless to provide any new information; it must be coupled with premises. And of course the problem becomes how to be certain of your premises; for if they turn out to be not true, deducing conclusions from them is a waste of time, Thus it is that deductive logic is not a great deal of use in dealing with things of this world; since very rarely are we 100 percent certain of our premises. Even if we think our premises have a 99 percent chance of being true, deduction is still useless, since it is not the case that our deduced conclusion must also have a 99 percent chance of being true.2

Of course, if you define your premises to be true, then deduction is very useful. This is the case with some mathematical problems, with law and with theology to mention three cases, each of which derives its first principles from an unquestionable source. If your premises are true, then sound deduction is held to always produce true conclusions.

It is this neat, cut-and-dried and mechanically efficient aspect of deductive reasoning that leads to the philosophy of rationalism. Rationalists (the two most famous being Plato and Descartes) hold that we can be totally and completely certain of some essential truths of this world by the use of deductive reason alone. On the surface this seems an attractive possibility, but the problems appear when we look for our premises. The enormous number of 'absolute and certain truths' propounded by rationalists from Plato to Descartes are often contradictory, mostly fanciful, and seldom of any practical use at all. This has tended to belittle the idea of rationalism, and deduction along with it. (It is interesting however to note that a form of rationalism is in vogue again due to the contemporary philosopher Chomsky. He sees his premises in the universality of some properties of language, which he thinks are determined by structures of mind which are common to all humans, and with which they are born.3)

However, even if deductive reasoning seemed unable after all to establish 'absolute and certain truths' about the world as we see it, its cold elegance and formal efficiency were still attractive to the philosopher searching for an unquestionable certainty to cling on to. This led to a fifty year spate (1879-1931) of renewed faith in deduction. For if the stumbling block of a rationalist's philosophy is the need to find premises, then (said the philosophers) let's do away with premises. And if you remove the premises you only have the deductive reasoning left; so, undaunted, logicians studied the bare bones of deduction.

Now this could only be done after the middle of the 19th century, when George Boole invented Symbolic Logic. This, as its name implies, means that instead of dealing with propositions (such as "All human beings are mortal"), one dealt with symbols only (such as 'A' or 'B'). Thus the truth or falsity of the premises becomes meaningless, and enables the relationships between them and rules of the logical process itself to be examined.

This new study was first turned to mathematics, and in 1879 it was suggested (by Frege) that in fact pure mathematics is a form of deductive reason alone; this led to an attempt to drain mathematics of any meaning so that mathematical expressions became a collection of empty signs (technically called 'meta mathematics'); and this in turn led to a famous work called 'Principia Mathematica' in 1910,4 which claimed to prove mathematics is nothing but deductive logic (ie it needed no premises except logic itself) and furthermore that everyday language has a similar basic structure. This was very exciting, since it was thus believed that this 'new' form of deductive logic would provide philosophy with a tool of razor-like sharpness for clarifying language and thus solving some of the age-old philosophical disputes. And the resulting philosophy of Logical Analysis (as it was called) was in some degree successful, though it led A.J. Ayer to remark that philosophy is now just "talk about talk".5

But in 1931 there was a bombshell. For then a young Austrian mathematician, Kurt Godel, published in an obscure scientific journal a cast-iron proof that no deductive logical system of any complexity was consistent.6 It is impossible to even think of simple arithmetic (much less pure mathematics) as reducible to deductive logic; you can bring in as many premises as you like, of whatever sort you like, but it is still impossible to have a complete and consistent deductive system.

While Godel's proof does not render deduction or even Principia Mathematica useless, what it does do is show that deductive logic cannot produce by itself an all-inclusive system of consistent 'truths'. Some 'truths' will get left out, and if you introduce more premises to account for them, then you are bound to produce contradictions in the other 'truths'.

Godel's work is brilliant, and it has stirred up a hornet's nest amongst mathematical logicians, nobody being certain any more of the basis of mathematics. But is has undoubtedly left deduction a very weak candidate for solving the problems with which this book is concerned.

iii) Induction

While deductive logic is concerned with arguing from the general to the particular, inductive logic is concerned with reasoning from the particular to the general. For example, I can state that if I hold my pen in the air and let it go, it will fall towards the ground. Now the truth of that statement does not come from deduction, but from induction. For I have no 'proof' that it will fall to the ground; I only think it will fall to the ground because in all the innumerable times I have let go of something in the air during my life, that something has invariably fallen towards the ground; and because it has happened so many times before, I feel it is bound to happen again. So strictly speaking, I cannot say, "I know, my pen will fall if I let it go," but only, "My past experience leads me to suppose that if I let my pen go there is a very great probability that it will fall down." Of course this latter statement is very ponderous, and if in everyday life we insisted on being absolutely correct and talking like this, we would be so pompous as to be unbearable; but nevertheless the latter statement is the correct one.

We can take another example. Suppose, as previously, we want to establish the truth of "All Englishmen are mortal." But now we do not want to use deduction, since although the deductive reasoning is valid, we are not sure of the premises; in particular, we do not accept the premise "All human beings are mortal." (After all one could only know this with certainty after every human being had died - which is certainly a problem if one includes oneself among the class of human beings.) So to establish "All Englishmen are mortal", we turn to induction, and argue from facts that we do know to be true, and argue from the particular to the general. For instance, we can say, "Every Englishman born before 1860 has died," and "Englishmen are still dying." These two statements are undoubtedly true, and they make it highly probable that my conclusion "All Englishmen are mortal" is true. This is induction. But notice that although my original two statements are 100 percent true, and the reasoning is sound, the conclusion is not 100 percent certain - it is only highly probable. (There may be an Englishman alive today who will never die.)

This is the hallmark of induction: that it cannot establish definitely true conclusions, but only conclusions which are probable. But unlike deduction, where the conclusions can be thought of as 'locked up' in the premises and have only to be 'led out', induction can give us fresh information about the world. In other words it can provide conclusions which tell us something new and original, but of course we have to pay the price that the 'truth' of the conclusions is only probable.

And just as deductive logic inspired a philosophy (rationalism), so inductive logic inspired a philosophy - empiricism. This scorned to produce 'absolute and certain truths' about the world via deduction, but tried to construct an account of knowledge in terms of sense experience via induction. In other words, from particular instances of what we experience through our senses, broad conclusions were established, which though only probable were nevertheless useful.7

Of course, scientific knowledge is largely gained by the use of induction; in fact science as we know it is often called 'empirical science'. It does not attempt to discover indubitable truths about the universe, but only to develop probable hypotheses. The empiricist claims that such hypotheses (though only high probable) are much more useful to mankind than all the alleged certainties of the rationalists.

The great 18th century philosopher David Hume claimed to show that in fact empiricism is not a sufficient basis for science, the whole thing resting on the shifting sands of uncertainty. Philosophers since have found it difficult to refute Hume's arguments. Scientists don't bother to try; they say that scepticism can be carried too far, and if you like you can find sufficient grounds for being uncertain about anything. The point is, they say, that empirical science and induction work; the results are useful in practice. In other words, they tell Hume and the sceptics to get lost.

But nevertheless, the fact remains, that for good or for ill, induction can never ever lead to 100 percent certainty.

The Scientific Method

We now turn from logic to the 'scientific method'.

It is difficult to define precisely what this is. Its object is to acquire knowledge of the world by simplifying the complexity we see around us; it requires in its practitioner a mixture of reasoning, the ability for controlled observation and patient experiment, a good pinch of imagination, and in some cases a fair bit of courage. It consists basically in patiently collecting a set of apparently unrelated facts of the universe and putting forward a unifying factor or common cause to explain them. This common cause is called the 'hypothesis', and it can be anything from an imaginative guess to a tediously reasoned conclusion. The hypothesis is then usually tested by reasoning what could be expected to happen if the hypothesis were correct, and then observing or experimenting to see if whatever it is actually does happen. If the hypothesis is confirmed in this way, and succeeds in explaining what were previously inexplicable observations, then it becomes dignified by the title 'theory'. Eventually it may even come to be known as a 'law'.

The beginnings of the scientific method can be traced back to the Greeks, but in modern times we can count Sir Francis Bacon as its founder. He attempted to systematise inductive reason and the scientific method in general. In true scientific spirit, he died in 1626 of a chill caught while experimenting on refrigeration by stuffing a chicken full of snow. The other important influence on the future course of science came from Descartes. He claimed to have thought of his philosophy while meditating in a kitchen stove (by contrast Socrates liked to meditate in the snow) and the resulting metaphysics gave science the go-ahead to dwell exclusively on the public world, as we saw in Chapter 4.

Anyway, in this section we will make just a few observations on the principle of scientific methods.

Firstly, from what has been said so far, we can see that the scientific method is a blend of discursive thought and a direct-externalist approach. The latter is essential, for the drudgery, endless patience and often acute boredom involved in scientific research and experimentation requires an unflagging direct-externalist attitude; since only when all hope of Peace is placed entirely in understanding the external world is it that the will-power will be generated to carry through the tediousness of much scientific work.

Secondly, being empirical, it rests largely on induction; in other words, it can be taken as a scientific 'law' that objects always fall to the ground when dropped because it has always been observed to happen. As we have pointed out, induction never leads to absolute certainty of a correct hypothesis, but a wrong hypothesis can be shown to be wrong with certainty. For instance, suppose I have an hypothesis, "The Sun rises in the West." Now just one instance of the sun rising in the East is enough to make it absolutely certain that my hypothesis is wrong. But if I put forward the presumably correct hypothesis, "The Sun rises in the East," then I can never be 100 percent certain of its correctness. However many times I observe the sun to rise in the East, strictly I can only state that it is highly probable that my hypothesis is correct. (I cannot be 100 percent certain that the sun will not rise in the West tomorrow.) Thus any empirical science can in fact only state with certainty what is not true, and cannot state with certainty what is true. As was mentioned in the last section, in practical terms this is unimportant, but it is nevertheless the case.

It is interesting to note that the Austrian born philosopher Karl Popper took this fact, that only negations of hypotheses could be claimed with certainty, for the starting point of his new approach to the scientific method.8 He hoped to build up a scientific method not based on induction; some think this is very successful, others do not. In practice, however, this is not very important, for although he encourages scientists to be critical of their own hypotheses and to try to negate them rather than prove them, nevertheless the result is the same - scientific 'facts' are only probabilities and not certainties. In fact, the intellectual history of mankind shows that most facts 'known to be true' at one time or another have turned out in the end to be false.

Popper holds that by negating our hypotheses we can, using imagination, progress beyond them and find hypotheses nearer and nearer the 'truth' (though we can never find an hypothesis or theory which is 'true', ie certain).

Indeed, the whole business of confirming hypotheses (which Popper rejects) is riddled with muddled thinking and bad reasoning. For a start, deduction is used considerably in the scientific method, mainly in the mathematical or verbal argument which leads either to the formulation of the hypothesis or the results which should lead from it. We have shown already that deduction can only be valid if the premises are 100 percent certain, and we have also shown that whereas scientific 'facts' are concerned, nothing ever is 100 percent certain. And since most deduced conclusions in science are based upon scientific 'facts', this speaks for itself. There is also the point that most sciences use mathematics, and as we have seen the foundation of mathematics is not at all well understood at the present time. This is particularly important in theoretical physics, for instance, where the mathematics used is very abstruse and complex.

Another very elementary mistake in the logic of the verification of hypotheses which is commonly committed, is that of "affirming the consequent". That is, I deduce from my hypothesis a conclusion, and because the conclusion turns out to be valid (by experiment) then I hold my hypothesis to be true. Suppose my hypothesis is "All Englishmen have wings"; now if I couple this with the statement, "All winged creatures eat food," then from these two premises it is valid reasoning to deduce "All Englishmen eat food." According to the scientific method, I examine my conclusion, and find that indeed all Englishmen do eat food, and so I can proclaim that my hypothesis ("All Englishmen have wings") is correct, because it leads to true conclusions. Thus the very foundation of the traditional scientific method is based on a fundamental logical error.

There are very many other examples, some very subtle, of the way incorrect logic is often used in scientific procedures. When we recognise the fact that in most scientific work many auxiliary hypotheses and results of other scientists are involved in the argument, it seems miraculous that the scientific method ever achieves any consistent results.9

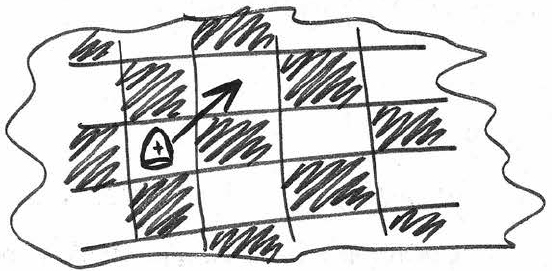

Another point about the scientific method is that to be useful, a discovery must be related to already existing theories. Whenever this does not happen, a discovery is 'ahead of its time' and is ignored; not because it is thought to be untrue, but because nothing can be done with it. One example of this is the discovery of gene in 1865 by Mendel; it was not until 1900 that related topics in biology had 'caught up' and so enabled his discovery to be used and thus accepted. Exactly the same thing occurred in 1944 when it was proved that DNA was the substance responsible for passing on hereditary information.10 Today, the outstanding example of this phenomena concerns ESP (extra-sensory-perception) and PK (psycho-kinesis).

For there is no doubt that ESP exists. Recently there has been such a spate of hard documentary evidence that no reasonable person can deny it.11 For instance, Russian scientists are conducting extensive experiments into telepathy and premonition, believed to be for military purposes. One cruel but conclusive experiment which a scientist called Popov conducted was to take some newly-born rabbits born in a submarine, keeping their mother on shore with electrodes in her brain. At intervals the underwater rabbits were killed one by one, and at the exact time that each of them died, there were sharp electrical responses in the brain waves of their mother.12 An investigator in America has even shown that plants have some perceptive faculties.13 It has also been conclusively shown that premonition and prophecy actually occur.14 There are even people who can photograph scenes from their sub-conscious mind,12 and also people who can photograph past events.15

In the field of PK we have Uri Geller bending forks and Edgar Mitchell of the Apollo 14 lunar expedition (who himself did unofficial ESP experiment during the flight) supporting him.16 While the evidence of some of these later findings is not accepted by some, surely no-one who looked at even a small part of the evidence accumulated over eighty years by the Society for Psychical Research could doubt that ESP and PR actually exist. (This is probably why so few do look at it.)

So if we assume that such phenomena do exist, and have been more than adequately verified, the question arises that why are they so persistently ignored by the scientific community in general? The answer is surely that just as with the discovery of the gene in 1865, or of the hereditary quality of DNA in 1944, they cannot be dealt with by the scientific method. The discoveries are 'ahead of their time' and cannot be welded onto the existing body of scientific knowledge as it is at this time. Maybe it is because of this limitation the scientific method imposes that scientists feel impotent to deal with the discoveries, and the result is an unreasoning denial of the facts. As the famous biologist Alexis Carrel says: "They (scientists) willingly believe that facts that cannot be explained by current theories do not exist." 17

There is just one more point to make before the end of this section, and that is that many scientists admit that their discoveries or hypotheses came to them not via the scientific method, nor even through their imagination, but through a definite 'insight', a sudden revelation when all became clear. Descartes reports that he discovered the essentials of analytical geometry in a dream, and similarly Kekule in 1865 had a vision in a dream of a snake biting its tail from which he discovered the ring-like structure of the benzene molecule. The archaeologist Hilprecht solved a Babylonian inscription in a dream, and the French mathematician Poincare states that he solved an abstruse mathematical problem when he was not thinking about it at all. He was boarding a bus, and in the instant that he put his foot on the step of the bus, the whole solution came to him with perfect clarity.18

Whether one chooses to explain these phenomena as intuitions from a higher state of consciousness, or as the unconscious quietly working on the data and presenting the answer on a plate to the conscious mind, is unimportant. It is a phenomenon which is unexpected, cannot be readily controlled, is just the opposite from discursive thought and is completely outside the scientific method

All the above points combine to make it appear that the scientific method is unsuitable for dealing with the subject of the investigation this book is concerned with.

Metaphysics

In this, the last section of this chapter, we look at metaphysics - not so much at the theories themselves, but more at the inherent limitations they possess on account of their being based on reason. Bertrand Russell defined metaphysics as an "attempt to conceive the world as a whole by means of thought",l9 and we will use his definition to work with. First however we will look back in history to the Greeks, with whom the 'attempt to conceive the world as a whole by thought' began (in the West).

The first western thinker to speculate about the nature of the world in a reasoned fashion is always held to be Thales of Miletus, from Ionia, who lived in the 6th century BC. For several hundred years afterwards metaphysics was a very popular pastime amongst the Greeks, reason and intellect assuming a greater and greater importance as time went by. In the 5th century BC we get Socrates, who was executed because his "search for Truth through reason unsettled young men's minds". Plato in the 4th century BC valued the intellect and reason even more, for while God is "the greatest, best, fairest, most perfect - the one only - begotten of heaven," He is nevertheless for Plato "the image of the intellectual".

After Plato we find Aristotle rationally dissecting the external world, classifying and dividing whatever he touched. Discursive thought reigned supreme - in fact God, the First Cause, is pure thought, "for thought is what is best."

The complete dominance of reason and the intellect were held to be amply justified by their fruits. We get Euclid's codifying of geometry which is one of the greatest achievements of Greek reasoning power, and in the 3rd century BC we get the complete Copernican theory of the earth orbiting the sun (put forward by Aristarchus of Samos) and we also get Archimedes, in the best scientific tradition, using reason to construct ingenious but fearful war-machines. After this, the great age of the emergence of the intellect was ended.20 Although the Greeks were intellectually great, they seemed to lack that patience and aptitude for sustained observation and experiment necessary for great scientific achievements

For instance, they almost invented the steam engine; a thinker called Heron had a hollow ball revolving rapidly due to pressurised steam, and while everyone agreed how powerful steam was and what fine things it could do, they did not follow it up with the practicalities necessary for developing steam power, as Watt did in an almost identical situation 2,000 years later.

But the question we are concerned with is how does 'conceiving the world as a whole by means of thought' lessen Unpeace? That the intellectual feats of the Greeks were great achievements is undisputed, but so what? Every schoolboy who studies the classics is brought up on the notion that Ancient Greece was a Golden Age, an age where Beauty and Truth were valued above all else. But if we look at history we see much ugliness and war; the Greeks were often fighting, either among themselves (eg Athens versus Sparta) or with others (eg the Persians). In particular, the so-called Hellenistic Age (c 350-100 BC) was an age of great turmoil and misery. After Alexander the Great died, there was almost continuous fighting over how to split up his vast empire. There was terrible cruelty and wide-spread discontent. Prices rose and wages fell, due largely to the influx of cheap eastern slave labour; and as Russell says of this period, "… fear took the place of hope; the purpose of life was rather to escape misfortune than to achieve any positive good."20 This only came to an end with the complete subjection of everybody by the Romans.

We dealt in Chapter with the lot of the common people in times of intellectual achievements in later centuries, including our own era, and so now we will go on to briefly mention some criticisms of the attempts to build up an intellectual understanding, of the world and of our place in it - ie a metaphysical system.

To begin with, it is worth noting that such systems have been constructed for over 2,000 years and after all this time there is no general agreement as to which of them (if any) are true. Moreover, each school of metaphysicians seems to be able to show the difficulties of all other metaphysical theories, but cannot justify its own theory satisfactorily. Thus the problem appears to be not the truth or plausibility of the theories, but the validity of the whole metaphysical enterprise itself.

One of the most damning investigations of the practice of metaphysics was carried out by the 18th century philosopher David Hume, the 'gentle sceptic'. We have mentioned him already in this chapter in connection with the shortcomings of induction and empiricism. Hume held that not only are the concepts employed by metaphysicians (eg 'reality', 'mind', 'substance', 'God', matter', etc) meaningless, but also the very questions that metaphysics tries to answer. For if our knowledge of the world only comes from what we experience, and the principle of induction has no rational basis and can never lead to 100 percent certainty (which Hume showed to be the case, based on a lengthy analysis of the cause-and-effect duality), then we have no intellectual certainty of anything - either in the public or the private world.

The key word in this last sentence is 'intellectual' - for Hume was the first to admit that we act, reason and believe as if many things were certain. What he is saying is that such certainty cannot be based on reason, but merely upon faith and experience. He writes, "The sceptic still continues to reason or believe, even though he asserts that he cannot defend his reason by reason." 21 It was because of this point that this book started with facts of experience, such as conflict and Unpeace, rather than 'facts' of reason, which can never be justified (by reason).

Thus for Hume the study of metaphysics became the study of metaphysicians; he wanted to know why supposedly sane and intelligent people discuss at great lengths questions which are only meaningless quibbles, and could not in any case be answered even if they were not. He would certainly have agreed with Adam's remark that philosophy (or to be precise - metaphysics) is "unintelligible answers to insoluble problems." 22

Hume's conclusions are echoed in some modern philosophical schools, such as the Logical Positivists and that of Popper. Many thinkers, including Russell, hold that no one has refuted these conclusions successfully; however, soon after Hume's death the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant claimed to have refuted him or - to be precise - his methods, since Kant agreed with Hume's final conclusion about metaphysics

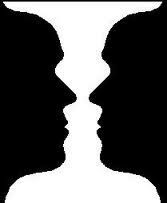

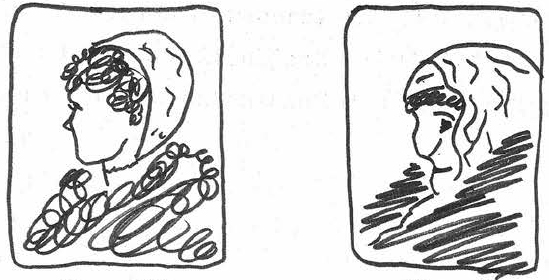

Kant agreed that all our knowledge begins with experience, but denied that it arises entirely from experience. He maintains that the sum total of our experience (which he called the 'phenomenal' world) is the product of two things - something we are presented with from 'outside' (the 'noumenal' world), and some inherent condition of the mind (called 'forms of intuition' and 'categories'). That which is presented from outside, the noumenal world, is the world as-it-is, but which we can never perceive. This idea can be expressed as an analogy of us looking through some coloured glasses which we cannot remove. What we see is then determined by the objects we are looking at and by the coloured glasses. The form in which we experience the object is determined by the glasses, but the actual content is determined by the object itself.

So according to Kant, the world as it 'really' is (the noumenal world) cannot be perceived (or even conceived) as it is by the senses or the intellect. When we look at it, we do so through the inherent 'forms of intuition and categories' in our minds, and so perceive something else - the phenomenal world. In our terminology, the phenomenal world (being what we actually experience) is both the public and the private worlds; Kant saw no need to distinguish them, since they are both objects of experience, and he lumped them together as the 'phenomenal world'.

On this type of argument, Kant claimed to show that Hume was wrong, and that we can have intellectual certainty about some things in the world, on account of having 'within' us the inherent 'forms of intuition and categories' which always determined the structure of our experience. To go into Kant's philosophy in detail is very complicated, and we will not do so here. It is, in fact, immaterial whether Kant disproved Hume or not for our purpose, since he went on in any case to support Hume's main conclusion - that metaphysics is a waste of time.

For while Kant thought (unlike Hume) that we could gain certain knowledge concerning the phenomenal world we experience, we can never experience or know anything intellectually at all either about the noumenal world (the world 'as it is') or about the basis of the forms of intuition and categories which we view things 'through'. Since it is the business of metaphysics to go beyond the world we merely perceive (the phenomena) and to explain the 'real nature' of things (the noumenal), then metaphysics is doomed to failure. The most we can do is to philosophise about the conditions that regulate our knowledge of the phenomenal world, a line taken up by many present-day philosophers, notably Wittgenstein in both his earlier thinking (Logical Atomism) and his later thinking which developed into the Ordinary Language school. Russell, for instance, (a logical atomist or 'analyst') says that logical analysis "confesses frankly that the human intellect is unable to find conclusive answers to many questions of profound importance to mankind." 23

Of course, there are still philosophers who have not abandoned the quest for metaphysical 'truths', in particular the existentialists and the associated school of 'phenomenology', but there is as yet no agreement on the validity of their results

Summary

In this chapter we maintained at the beginning that the activity of the intellect, discursive thought, is inherently and in theory unable to extricate us from Unpeace. This was backed up by the following conclusions concerning three main intellectual disciplines:

1) In the realm of reason or logic we showed that

- i) the basic principle of reason did not apply to some external objects (eg sub-atomic particles, and also art, love etc),

- ii) deduction is not very useful in practical matters,

- iii) that no complex system is completely deductive anyway (Godel's proof) and

- iv) that induction can never give absolutely certain conclusions

2) As for the scientific method, we showed that

- i) nothing is ever certain (both traditionally or according to Popper),

- ii) that no completely new result can be assimilated, and

- iii) that insight, which is completely outside the scientific method, is often used.

3) In the realm of metaphysics we saw how it is impossible to understand the world as it is through the intellect, either from Hume's or Kant's arguments.

8 - Intellectual Unity

In the last chapter we showed that thought by its very nature of being discursive is incapable of breaking through the difference we find all around us; it is only fitted to deal in duality and not beyond. This was also suggested back in Chapter 2 on separateness, where we said that any unity we perceive must be in terms of difference.

In spite of all this, of course, we think about unity quite a lot. After all, if Unpeace is the result of being bound to the world of difference, and the fundamental urge in us is to avoid Unpeace, then obviously we will be attracted to any thought or theory which gives prominence to non-difference or unity.

In this chapter we will look at some of the attempts that have been made to intellectually construct and conceive of unity from the sea of difference we find all around us. We will deal mainly with concepts in modern science, especially that of 'superspace' and the 'bootstrap', and finally consider briefly some theological arguments for unity.

Scientific Unity

Although we have been at pains to show that science deals in difference, as it were, and in fact tends to enhance difference through classifications and analysing, there are nevertheless some strong impulses in science to find unity.

For instance, a successful scientific theory is one which explains a wide range of previously unconnected events; it establishes a principle from which many diverse phenomena follow. In this sense, science is striving for unity; there seems to be a deep-rooted urge to unify all the many differences. An excellent example of this is in Newton's laws of motion, mentioned in Chapter 6. From these three laws, every problem in mechanics and dynamics could (in theory at least) be solved; they were staggering in their simplicity, and in the fact that they could account for so many completely different phenomena. But at the end of the 19th century some phenomena were observed which Newton's laws could not explain - the unity had broken down. So a new theory was needed; one that could unify and explain not only all the phenomena explicable in terms of Newton's laws, but also the awkward new phenomena. Such a theory was proposed by Einstein in 1905 (the Special Theory of Relativity), and it succeeded in restoring the lost unity of mechanics and dynamics.