The tale is stranger than fiction. Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, a guru from India, gathered 2,000 followers at a remote Eastern Oregon ranch. Arriving in search of enlightenment, the Rajneeshees became a political and social force that collided with traditional Oregon. Ultimately, the conflict led to attempted murder, global manhunts and prison time. Twenty-five years later, long-secret government files and now-talkative participants make it clear that things were far worse at Rancho Rajneesh than many realized.

Part 1 - 25 years after Rajneeshee commune collapsed, the truth spills out

Part 1 - 25 years after Rajneeshee commune collapsed, the truth spills outRajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: After a quarter century, a fuller and more bizarre account emerges of the deceptive and dangerous goings-on at Rancho Rajneesh in rural Oregon.

Part 2 - Thwarted Rajneeshee leaders attack enemies, neighbors with poison

Part 2 - Thwarted Rajneeshee leaders attack enemies, neighbors with poisonRajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: As land rules keep Rajneeshees from building the utopia they envision in the 1980s, they go from dirty tricks to biological warfare.

Part 3 - Rajneeshee leaders take revenge on The Dalles' with poison, homeless

Part 3 - Rajneeshee leaders take revenge on The Dalles' with poison, homelessRajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: In the mid-1980s, Rajneeshee operatives unleash a secret weapon in The Dalles and import homeless people to get an electoral edge.

Part 4 - Rajneeshee leaders see enemies everywhere as questions compound

Part 4 - Rajneeshee leaders see enemies everywhere as questions compoundRajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: As problems grow for the Rajneeshees in 1984, an increasingly unstable Sheela continues her vicious campaign against enemies.

Part 5 - Rajneeshees' Utopian dreams collapse as talks turn to murder

Part 5 - Rajneeshees' Utopian dreams collapse as talks turn to murderRajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: In 1985, the Rajneesh commune dissolves after death plots and botched assassination attempts target outsiders and insiders alike.

Part 1 - Ma Anand Sheela: Rajneeshees' public face left Oregon but holds onto blame, bitterness

Part 1 - Ma Anand Sheela: Rajneeshees' public face left Oregon but holds onto blame, bitterness

Rajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh's former-aide, now running care homes for disabled in Switzerland, will not discuss her crimes.

Ma Anand Puja stepped into St. Vincent Hospital on a summer night in 1985, hunting for James Comini.

The Filipino nurse was there to kill the rural Oregon politician, who was recuperating from ear surgery at the Portland hospital. She carried a syringe to inject a mixture into Comini's intravenous tube that would stop his heart.

But once inside Comini's seventh-floor isolation room, Puja discovered her target wasn't on an IV. Flustered, she hurried from the hospital to a getaway car, and her assassination team started the long drive home.

Their destination: Rancho Rajneesh, a spiritual encampment 200 miles away in eastern Oregon. It was base for Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, a guru from India, and 2,000 of his worshippers.

The murder scheme was just one of many increasingly desperate attempts to save the guru's empire.

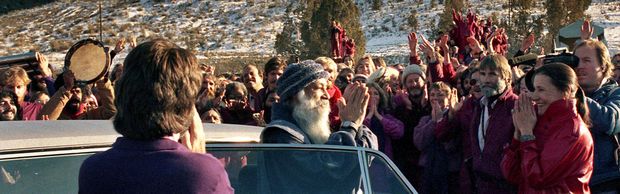

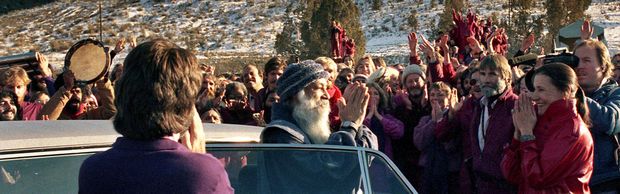

The Rajneeshees had been making headlines in Oregon for four years. Thousands dressed in red, worked without pay and idolized a wispy-haired man who sat silent before them. They had taken over a worn-out cattle ranch to build a religious utopia. They formed a city, and took over another. They bought one Rolls-Royce after another for the guru -- 93 in all.

Along the way, they made plenty of enemies, often deliberately. Rajneeshee leaders were less than gracious in demanding government and community favors. Usually tolerant Oregonians pushed back, sometimes in threatening ways. Both sides stewed, often publicly, before matters escalated far beyond verbal taunts and nasty press releases.

Three months after the aborted Comini plot, the commune collapsed and the Rajneeshees' darkest secrets tumbled out.

Hand-picked teams of Rajneeshees had executed the largest biological terrorism attack in U.S. history, poisoning at least 700 people. They ran the largest illegal wiretapping operation ever uncovered. And their immigration fraud to harbor foreigners remains unrivaled in scope. The revelations brought criminal charges, defections, global manhunts and prison time.

But there was much more.

Long-secret government files obtained by The Oregonian, and fresh interviews with ex-Rajneeshees and others now willing to talk, yield chilling insight into what went on inside Rancho Rajneesh a quarter-century ago.

It's long been known they had marked Oregon's chief federal prosecutor for murder, but now it's clear the Rajneeshees also stalked the state attorney general, lining him up for death.

They contaminated salad bars at numerous restaurants, but The Oregonian's examination reveals for the first time that they just as eagerly spread dangerous bacteria at a grocery store, a public building and a political rally.

To strike at government authority, Rajneeshee leaders considered flying a bomb-laden plane into the county courthouse in The Dalles -- 16 years before al-Qaida used planes as weapons.

And power struggles within Rajneeshee leadership spawned plans to murder even some of their own. The guru's caretaker was to be killed in her bed, spared only by a simple mistake.

Strangely, most of these stunning crimes were in rebellion against that most mundane of government regulations, land-use law. The Rajneeshees turned the yawner of comprehensive plans into a page-turning thriller of brazen crimes.

A new start

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh needed a new place to build his worldwide commune.

In India, he worked as a small-town philosophy professor until he found enlightenment paid better. He built a thriving enterprise attracting Westerners to his lectures and group therapies. They sought meaning in their lives, escaping the remains of the Vietnam War and a crashing world economy. And Rajneesh mixed in plenty of sexual freedom, ensuring publicity to build his brand.

Government authorities in India, weary of the Rajneesh's growing notoriety, cracked down on his group's unseemly and illegal behavior, including smuggling and tax fraud. The guru ran, ending up half a globe away at the Big Muddy Ranch, 100 square miles of rangeland an hour's drive north of Madras.

The first contingent of Rajneeshees quietly moved to Oregon in summer 1981, but they couldn't escape notice for long. Part of the guru's brand was clothing in reddish hues. Such dress was out of place in the blue denim reaches of Oregon. Followers, known as sannyasins, also displayed their devotion to the guru by wearing malas, wood bead necklaces holding a photo of Rajneesh.

Resettling in Oregon was the work of his chief of staff, Ma Anand Sheela, then 31 years old. She was a native of India, born to a privileged family as Sheela Patel. She wasn't after enlightenment. She was quick-witted and hungry for power, the perfect instrument for the guru's ambition.

Initially soft-spoken and engaging, Sheela charmed Oregon ranchers and politicians. Early on, she hosted a dance in Madras where cowboys partied until dawn. She curried favor, buying 50 head of cattle from a Wasco County commissioner, even though the commune was vegetarian.

She assured the guru that the commune of his dreams would soon rise on the Big Muddy. She expected to put up housing compounds, warehouses and support buildings. Business enterprises, once based in India, would move to the ranch.

In short, Sheela intended to do as she wished on their remote 64,000 acres.

Anxious to move ahead, she closed the property deal without understanding Oregon law -- a pivotal mistake. She didn't know the state severely limited how many people and buildings could be jammed onto ranch land.

Already it was too late. The money was paid, the guru packed and hundreds of sannyasins were expecting to be housed and fed. Sheela and the guru were undeterred. In India, trickery and bribery got results. Why would Oregon be any different?

In the ensuing months, Durow repeatedly traveled to the ranch to monitor developments. He discovered that four-bedroom modular houses were in fact dorms with no kitchen, no living room. The Rajneeshees, on alert for his visits, routinely hid extra mattresses to disguise the true population at the ranch.

Making enemies

To legally stretch the limits, the Rajneeshees moved to form their own city.

Their private Portland lawyers advised they needed to befriend 1000 Friends of Oregon. The environmental group was a watchdog over land use, especially guarding farmland from development.

In late 1981, Sheela, Krishna Deva -- better known as KD -- and others from the commune met with two lawyers from 1000 Friends. They explained they needed to erect a city to tend to the thousands who would be moving there. They explained that remaking the ranch into a working farm was a bigger task than expected.

The environmental lawyers applauded the desire to restore the land, but they saw no need for a city. Plopping an urban area into the middle of an agricultural operation didn't make sense. As their resistance became apparent, Sheela asked whether their opposition would dissolve if the Rajneeshees joined 1000 Friends with a substantial contribution.

The bribe was brushed off. Sheela turned snide. Observing the modest furnishings in the Portland office, Sheela said she wasn't surprised by "shabby" work being done by people working in "shabby" surroundings. The crack was needless, but it was trademark Sheela.

From then on, 1000 Friends and the Rajneeshees battled. The organization launched an aggressive, but not always successful, legal campaign to blunt creation of the city. Its fundraising literature soon bore the picture of Sheela, and donations and membership soared.

In turn, the Rajneeshees portrayed 1000 Friends as a pawn of powerful political interests. They considered the environmental group an enemy, more interested in crushing a religion than protecting land. They named their sewage lagoon after the group's executive director.

Their fight would rage on for years.

Much of it played out in Oregon courtrooms and in the media. Coached by the Bhagwan, Sheela became adept at using the press to her advantage. She could be counted on for outrageous news conferences, where her sharp tongue cut into the enemy of the day. She seemed to spit insults with every breath.

But her conduct troubled other Rajneesh leaders.

KD complained in a letter to the guru that the insults were impairing efforts to build the commune. The guru's response was blunt: You're a coward. KD swallowed the insult and kept his place at the inner circle of the ranch. Later, he used his insider knowledge to get a lenient plea deal for himself -- and to help send Sheela to prison.

Another insider, Ma Yoga Vidya, a mathematician then also known as Ann McCarthy, tried her hand at reeling in Sheela. In a private meeting with the guru, she described Sheela's conduct as "outrageous" and harmful to the commune. The guru nodded as he listened, but otherwise made no reply.

Her end run enraged Sheela. The next day, Sheela dragged herself out of a sick bed and, with an intravenous drip line in tow, took Vidya back to see the guru. This time he had plenty to say. He unloaded on Vidya, who was the commune president. He said Sheela was his agent, and when she spoke, she was talking for him. He told Vidya to never challenge Sheela and to share that instruction with other commune members.

Most Rajneeshees would have been surprised to learn the guru provided such intimate oversight. They believed the guru was a spiritual master, a rare enlightened man untouched by daily events at the ranch. To this day, some former sannyasins hold the view that he knew next to nothing about what was happening at his commune.

Sannyasins well understood, though, that Sheela acted with the guru's authority. She wasn't to be questioned on any decision or directive. She wielded the authority without restraint, sharing it with an elite team of other women leaders, called "moms" by their underlings, who kept the Rajneeshees in line both with favors and punishment.

Cliques and cracks

Not everyone could be so readily controlled, such as the guru's personal doctor, dentist and caretaker.

They and a handful of other sannyasins served Rajneesh in his fenced compound called Lao Tzu. Their independence irritated commune leaders, but especially peeved Sheela.

A group of wealthy California donors also proved challenging to control once they moved to the Oregon ranch in 1984. The most notable were Francoise Ruddy, whose former husband produced "The Godfather," and John Wally, a physician who made a fortune in emergency room medicine. She became Ma Prem Hasya; he was Swami Dhyan John.

They had no zeal for the lifestyle of seven-day workweeks, shared meals or rudimentary sleeping quarters. Instead, the Californians set up a home for themselves apart from the usual housing. They brought in expensive furnishings, artwork and even their own car, a Jaguar. Almost daily, they drove to Madras for groceries to avoid the ranch's staid meals.

That was bad enough, but they also attracted the guru's attention. They obliged him with diamond-studded watches and Rolls-Royces. Before long, Hasya married the guru's doctor.

The Hollywood group and the guru's personal staff soon made Sheela's list of people on and off the ranch considered a threat to the commune and the guru. She split up the Hollywood group, scattering them to separate homes around the ranch. She tried to replace the guru's doctor.

To keep tabs on what was going on inside the guru's compound, she had the place laced with hidden microphones and recording equipment. One bug was placed on a table leg next to the guru's favorite chair. He was told it was a panic button. Trusted sannyasins monitored the eavesdropping equipment, reporting information to the commune's top four leaders.

Eventually the chasm between the commune's leaders and the guru's chosen insiders became too much even for him. On a spring evening in 1984, he summoned both sides to his house and, in front of them all, lectured Sheela. He told her his house, not hers, was the center of the commune.

He turned to the others with a warning.

"Anyone who is close to me inevitably becomes a target of Sheela," the guru said.

He proved prophetic.

Two of those sitting at the guru's feet that day were later marked for death.

-- Les Zaitz: email him at specialreport@oregonian.com; visit the Rajneesh Report page on Facebook

Rajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: As land rules keep Rajneeshees from building the utopia they envision in the 1980s, they go from dirty tricks to biological warfare.

The call from home jolted Bill Hulse, a Wasco County commissioner and wheat rancher.

His wife, Rose, was panicked. Two Rajneeshees had driven up their dead-end street in Dufur, parked across from their house and sat there. One hour. Two hours. Four hours.

Hulse called police but was told their hands were tied. Parking on a public street wasn't illegal.

Such intimidation no longer surprised local officials, and leaders of the religious sect made no apologies.

The Rajneeshees wanted to be left alone to build their global commune. That ambition was being thwarted by regulators, politicians and nearby residents. Commune leaders fought back in ways large and small, public and clandestine. They did so in the name of their spiritual master, the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

Public opinion was initially divided as Gov. Vic Atiyeh tried to counsel tolerance.

From the time the group arrived in 1981, Atiyeh fielded scores of letters from Oregonians alarmed by the commune's development. Other citizens wrote their governor that the state should be more welcoming of a religious order.

Atiyeh responded to all with reserve. Typical was one letter to a Portlander: "Regardless of the religious beliefs or practices of this group, they are entitled to every right afforded under our Constitution." His duty, he said, was to protect those rights.

Retaliation grows

Dan Durow, the Wasco County planning director, was closer to the front lines, deciding almost daily what the Rajneeshees could and couldn't do on their land.

He was suspicious, since they had lied about their intentions in their first meeting with him. Still, he knew his every act would be closely watched, both by sharp Rajneeshee lawyers and their equally attentive legal opponents. He decided to administer land-use rules to the letter of the law, giving up the sometimes informal way rural counties handled such matters.

That strict compliance riled Rajneeshees, who felt Durow was deliberately impeding their efforts. They belittled him in meetings and in letters. On two occasions when he arrived for inspections, ranch equipment blocked the way, disabled by contrived breakdowns. Packs of Rajneeshees came to his office in The Dalles, disrupting work by scattering throughout workstations off-limits to the public.

Their aggressiveness alarmed Durow, and he worried for his safety. Uncertain what was coming, he sent his three young children to live out of town with their mother, his ex-wife.

At the commune, Rajneeshee leaders cast any resistance to their needs as oppression or religious discrimination.

They retaliated in petty ways. One Rajneeshee put a nail under the tire of a Wasco County planner while he attended a conference in Eugene. Ma Anand Sheela, the guru's top aide, held a courthouse door open for the state's deputy attorney general, his arms full of legal books. As he passed, she stuck out her foot, sending him sprawling to the ground to laughter from the Rajneeshees.

Such tactics, of course, didn't slow the growing government reaction to what was happening at Rancho Rajneesh. Durow and others held up, or denied, permission for some buildings, including a hospital. Then-Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer pressed his case to have the sect's city declared illegal.

Those obstacles undermined Sheela's power in the sect, derived in large measure from her promise to build a sprawling utopia. The guru pressed her relentlessly to sweep the hurdles away. Millions of dollars were at risk if their American dream failed.

Impatient with court action and petty pranks, Sheela set up secret squads to strike at the commune's enemies. These were disciples who accepted Sheela's view that the commune and their guru were in danger. Sheela, effective as any spy master, compartmentalized her minions. They operated alone, or in small teams, often unaware of one another's assignments.

Poison was the primary weapon, crafted by Ma Anand Puja, a nurse also known then as Diane Onang.

She was Sheela's shadow. The two had been close since their days in India, and Puja now supervised the ranch's medical department. She managed routine medical care but also ordered renegade Rajneeshees into isolation on trumped-up diagnoses and routinely overruled the sect's physicians. Daily, she medicated Sheela for stress.

From time to time, Puja retreated to a laboratory hidden in a cabin up a canyon on the ranch to secretly experiment with viruses and bacteria. Sheela wanted something to sicken people.

In summer 1984, Puja field-tested her work, handing unlabeled vials to those on the secret teams.

The operatives knew, or suspected, the brown liquid was salmonella, which produces severe diarrhea and other symptoms. Over months, they were dispatched to spread the poison in The Dalles. They initially hoped to sicken public officials standing in their way, but then pursued a grander scheme to attack innocent citizens.

Swami Krishna Deva, mayor of Rajneeshpuram, smeared Puja's mixture onto fixtures in the men's restroom at the Wasco County Courthouse in The Dalles.

Ma Dhyan Yogini, also known as Alma Peralta, went to town with vials in her purse. She stepped into a local political rally and took a seat. She secreted some of the contaminant on her hand, turned to an elderly man sitting next to her and shook hands. She also made her way into a nursing home in The Dalles, but her plan to contaminate food was disrupted by a suspicious kitchen worker.

Sheela tried her hand at contamination as well, taking a half-dozen Rajneeshees, including Puja, to a grocery store in The Dalles.

"Let's have some fun," Sheela said.

The group spread across the store with Sheela targeting the produce section, pouring brownish liquid from the vial she had hidden up her sleeve.

When there were no public reports of anyone getting sick, Sheela pushed Puja to find a more toxic solution.

About that time, Hulse and two other Wasco County commissioners arrived at the ranch for a tour. They parked Hulse's car outside the commune's welcome center and loaded into a commune van for their visit. When they got back, Hulse's car had a flat. The Rajneeshees arranged a repair on the spot that would cost Hulse $12.

As the commissioners waited in the hot August sun, Puja approached, offering each a glass of water. Her gesture was odd, for Puja was in her medical whites and had no role as a greeter.

The thirsty men took the water.

-- Les Zaitz: email him at specialreport@oregonian.com; visit the Rajneesh Report page on Facebook

Rajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: In the mid-1980s, Rajneeshee operatives unleash a secret weapon in The Dalles and import homeless people to get an electoral edge.

Unbearable stomach pain roused Bill Hulse from sleep.

The Wasco County commissioner ran for the bathroom, vomiting. His worried wife insisted he go to the hospital, where doctors admitted him as they tried to diagnose what was wrong.

Two hundred miles away in a mountain cabin at Camp Sherman, a second Wasco County commissioner awoke, ill. Ray Matthew stayed in bed, alone, for two days, unsure what was causing his violent sickness.

But a handful of Rajneeshees knew. The men had been poisoned the day before as they toured the religious sect's ranch, drinking down potent bacteria stirred into their water.

Hulse remained in the hospital four days, with doctors telling him he would have died without treatment. As he recovered at home later, Hulse concluded the Rajneeshees poisoned him. He said so publicly.

Rajneeshees reacted indignantly to his claim, saying there was nothing wrong with the water. "It was a simple act of human kindness on that sweltering day," a Rajneeshee PR person wrote to Hulse. "Now you are making a hysterical accusation that you were poisoned."

It wasn't until the commune collapsed a year later that Rajneeshee operatives admitted Hulse was right.

The poisoning was revenge for Wasco County's restricting growth at Rancho Rajneesh. The sect's leaders hoped sickening public officials would deter future decisions against their operation.

Yet the guru they worshiped, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, pushed for even more extreme acts.

His chief of staff, Ma Anand Sheela, shared with her inner circle that the guru was fed up with Wasco County's attitude. He wanted his people to get a seat on, or even get control of, the county's board of commissioners. That would at least give the commune a direct voice in its fate.

City under siege

Sheela conspired to make it happen. One Rajneeshee, shedding any trace she was affiliated with the ranch, moved to The Dalles intending to run for county office.

To elect her, the Rajneeshees hit upon two schemes. One was to depress the turnout by traditional Wasco County residents by making them sick. The second was to pack the rolls with new voters loyal to the Rajneeshees.

They first considered contaminating The Dalles' water supply. Operatives obtained maps of the water system and scouted reservoirs. But no one could figure a way to introduce enough contaminant to sicken people.

They decided instead to attack people where they ate: the restaurants of The Dalles. A young woman named Ma Anand Ava, one of Sheela's most reliable associates, was ferried to town by a driver who had no idea of her mission. She ordered him to stop at one restaurant after another, having him wait while she went in for a few moments at each stop.

Wearing a wig and dressed in street clothes, Ma Anand Puja -- who oversaw the commune's medical operations -- went on a separate mission, settling into a restaurant for lunch. Her companion helped himself to the salad bar and then watched, horrified, as Puja poured a liquid onto salad greens. She returned to her seat, calmly finishing her own lunch.

For residents and travelers exiting Interstate 84, going to any of 10 restaurants was routine.

Terry Turner, a local furniture store owner, took his wife and 2-year-old to Sunday brunch at a restaurant on the banks of the Columbia River. They enjoyed a casual meal, opting for the salad bar.

Across town, state Trooper Rick Carlton had the day off. He took his wife, 3-year-old son and 4-month-old baby to a downtown restaurant. After a meal that included a trip through the salad bar, they drove home.

By the next morning, both men were violently ill. So were Turner's young daughter and Carlton's son. Turner headed to a medical clinic, only to discover a waiting room filled with people just as ill.

"Where did you eat?" a nurse asked Turner.

"What?" he asked, confused by the question.

The nurse asked again, and when Turner told her, she said, "We've heard that several times."

Carlton tried going to work despite not feeling well, but soon clocked out for home, nauseated and weak. At home, he found his wife and son as sick as him. His mother-in-law drove up the Columbia River Gorge from Portland to tend the sick family.

Such scenes played out up and down the gorge. Soon, it was evident hundreds were sick. Hospital emergency rooms and medical clinics overflowed with people suffering nausea, diarrhea and enduring weakness.

"Rajneeshees," some whispered, but there was no proof.

A state health official famously concluded that restaurant workers in different restaurants had all ignored proper hygiene at the same time. Evidence of the Rajneeshees' true role wouldn't come out until the commune collapsed.

Using the homeless

Rancho Rajneesh faced an unfolding disaster of its own.

Using Sheela's American Express card, Rajneeshees had chartered buses in cities coast to coast, filling them with homeless people, mostly men. They said hauling them to Rancho Rajneesh was a humanitarian initiative. Those lured to the buses were promised food, beer and rest.

In truth, this was the second prong of the election scheme.

As the homeless rolled onto the ranch, they were obliged to register to vote. They were expected to vote the party ticket, as it were, when it came time to pick the new county commissioners.

But Rajneeshees quickly discovered many of the homeless had serious mental problems. A remote ranch founded on love and freedom was no place for an unruly mob. Fights broke out. To regain control, Rajneeshees injected the tranquilizer Haldol into beer kegs used to serve the homeless.

Eavesdroppers monitoring the ranch's bugged public pay phones recorded one of the homeless men apparently planning to kidnap the guru.

Sannyasins identified him as Felton Walker and took him to the Rajneeshee medical clinic, supposedly to be tested for tuberculosis. But the clinic had been emptied of all other patients by the time he arrived.

Walker changed into a hospital gown and lay on an examining room gurney. Someone taped Walker's arm to the gurney rail, and Puja put him to sleep with an injection. Then a Rajneeshee doctor administered sodium pentothal, the so-called "truth serum." Sheela and at least six other commune insiders gathered around Walker, slapping him awake to endure questioning about the plot. A tape of the call was played for him over and over. Walker kept dropping off to sleep, and his interrogators kept rousing him.

The episode went on for hours. About 3 a.m., the interrogators gave up after learning little of use. They kept Walker sedated for two more days before booting him off the ranch.

Soon, scores of homeless followed Walker. At first, they got bus tickets to return to their home cities. The Rajneeshees soon stopped that. Instead, they ferried the homeless to small towns around the commune and left them. Streets in towns such as Madras filled with penniless people far from home.

The spectacle deeply worried state and local authorities. They feared locals would be so angered by the callous act that they would strike out at the commune. The Oregon State Police and the National Guard devised contingency plans, with Guard commanders promising the governor they could mobilize 10,000 soldiers if necessary.

Sheela saw opportunity in the crisis and decided to negotiate for what she wasn't getting through the courts or crime. She sought meetings with Gov. Vic Atiyeh and Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer, inviting the governor to the ranch.

Neither man agreed, but when Sheela persisted, Atiyeh agreed to let his staff meet with her. The commune was dominating ever more of his time. And now the impending flood of homeless people into Oregon communities was pressing the tolerance of the state and its people to the breaking point.

Atiyeh hoped conversation would calm the charged atmosphere.

Sheela needed less than an hour to crush that hope.

-- Les Zaitz: email him at specialreport@oregonian.com; visit the Rajneesh Report page on Facebook

Editor's note: In a nearly unbelievable chapter of Oregon history, a guru from India gathered 2,000 followers to live on a remote eastern Oregon ranch. The dream collapsed 25 years ago amid attempted murders, criminal charges and deportations.

But the whole story was never made public. With first-ever access to government files, and some participants willing to talk for the first time, it's clear things were far worse than we realized.

What follows is an inside look -- based on witness statements, grand jury transcripts, police reports, court records and fresh interviews -- at how Rajneesh leaders tried to skirt land-use and immigration laws only to have their schemes collapse to the point they decided killing Oregonians was the only way to save their religious utopia.

Rajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: As problems grow for the Rajneeshees in 1984, an increasingly unstable Sheela continues her vicious campaign against enemies.

In fall 1984, Ma Anand Sheela believed she had leverage to play "Let's Make a Deal" with Oregon's governor.

She wanted Vic Atiyeh, a Republican in his second term, to dispose of three major problems facing the Rajneeshees.

In turn, she would dispose of a problem facing the state -- what to do with thousands of homeless men imported to Oregon in an attempt to swing local elections, but now being discarded to surrounding towns by the Rajneeshees.

She couldn't get an appointment with Atiyeh, but his chief of staff, Geraldine "Gerry" Thompson, arranged for a secret night meeting at a state office building in downtown Portland.

Thompson arrived with the head of the Oregon State Police, who discreetly placed officers around the building. Sheela arrived with Swami Krishna Deva, mayor of Rajneeshpuram and part of the commune's dirty tricks squad.

Thompson, well aware of Sheela's volatility, set the rules. There would be no shouting. There would be no profanity.

Sheela launched into her demands.

She wanted the governor to help clear visa troubles so her guru could avoid deportation. She wanted the state to drop its court case seeking to disband their city of Rajneeshpuram. And she wanted land-use obstacles removed so their compound's construction could continue apace.

In turn, she said, the Rajneeshees would help get the remaining homeless back where they came from.

Acting with Atiyeh's authority, Thompson said no deal. Growing angry, Sheela became abusive and profane.

Thompson finally slammed her palm on the desk. "That's it! Meeting over." Sheela sulked out into the hall, spewing invective.

But Krishna Deva, better known as KD, poked his head back into the office and told Thompson, "Just keep talking to us." The two set up a private link, and from then on he kept Thompson informed of the most intimate details of what was happening at the ranch, including the escalating danger.

Alarm among Sheela and her elite deepened. She secured their loyalty with privileges no one else in the commune had: private rooms, cars, special clothing. Together, they perceived ever-increasing threats from outside and from within.

They feared their guru would be harmed by vigilantes or arrested by authorities in what they were sure would be an unlawful act. They feared losing their own special places in the sect.

Their apocalyptic view wasn't shared by ordinary sannyasins, who were focused on the daily work, meditation and devising a life intended to be a global model. They didn't share in Sheela's paranoia, and some were embarrassed by her public tirades.

But most watched without protest.

They knew Sheela and her executive staff quickly punished doubters and challengers. Rank and file could be moved without notice to a new home or job. One of the commune's top lawyers crossed Sheela and soon found himself driving a bulldozer.

The most-feared punishment was banishment.

Complaining sannyasins were told they could -- or must -- leave the commune. To get there in the first place, however, worshippers typically sold all their possessions, donated most of their money to the commune and severed ties with outside families and friends.

Most truly believed Rancho Rajneesh was their home for life. Where would they go if that was taken away?

Arson squad

By late 1984, Sheela and her team were more isolated than ever.

They were exhausted. To keep going, Sheela relied on a regimen of medications. Nervous energy so robbed her of sleep that she resorted to a drip line for sedation. For her and the others, the exhaustion made their demons loom more menacing than ever.

One was Dan Durow, the Wasco County planner whose enforcement actions slowed or stopped construction at the ranch. They were particularly concerned that he had documented illegal construction at the ranch.

In her fatigue-fogged brain, Sheela reasoned that Durow couldn't act against the commune if his office was destroyed. Late one winter evening in early 1985, Sheela gathered with a half-dozen others to go over photographs and maps of the house that had been converted into offices for the Wasco County Planning Department. They decided to torch it.

Sheela called on trusted operatives: Ma Anand Ava, born Ava Avalos, and Ma Dhyan Yogini, born Alma Peralta; and Swami Anugiten, an arborist previously known as Richard Langford. The team used phony names to rent a Portland apartment as a safe house and recovered a Buick stashed at the airport for such missions.

Ava drove the team east on the freeway to The Dalles and about midnight dropped off Yogini and Anugiten just blocks from Durow's office. The two pried open a window, crawled inside and closed the drapes.

For about an hour, Yogini and Anugiten rifled through cabinets and desks, scattering government papers all about. To start the fire, they placed eight candles inside cardboard squares soaked with lighter fluid. The pair intended the candles to act as timers, igniting the cardboard once they burned down. The two arsonists lit the candles, crept back out the window, and closed it. But that starved the candles of oxygen, and only two fires started.

On their drive back to the safe house, the arsonists tossed their clothing, tainted with lighter fluid. In Portland, they called a ranch leader in a prearranged signal that meant "mission accomplished."

Back in The Dalles, a passing motorist called in the alarm, and firefighters quickly extinguished the flames before there was much damage. The heat melted part of the Planning Department's main computer, but the hard drive remained intact. Some papers burned, and others were damaged by water. But Durow and his crew were back in business within two weeks.

Legal setbacks

The Rajneeshees were no more successful later that May in trying to derail a state hearing that was exposing improper construction at the ranch. The state claimed the commune illegally wired 600 tents in preparation for a world festival.

The hearing was in a conference room at the State Library in Salem. A Rajneeshee contaminated unattended drinking water with an overdose level of Haldol. On one day, the state's chief electrical inspector got sick. The next day, Assistant Attorney General Karen Green had trouble during questioning as her jaw inexplicably froze.

When the session ended for the day, Green's two-block walk to her office became a half-hour ordeal. Her feet and legs, coursed with Haldol, cramped so much she froze in place.

But the poisonings didn't alter the outcome. The hearings officer proposed a $1 million fine against the commune for the wiring.

At the same time, federal prosecutors continued their now-relentless investigation into immigration fraud among Rajneeshees. A grand jury met for long hours, facing a deadline to indict soon or go home. The Rajneeshees monitored the secret work as best they could, growing alarmed when a loose-tongued federal mediator told them the guru himself could face criminal charges.

On the state front, Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer was winning round after round in his effort to declare Rajneeshpuram an illegal city. The commune's entire legal staff trooped to the guru's compound for guidance at one juncture. Advised the case was a losing matter, the guru instructed the lawyers to soldier on. Losing the case, though, meant losing the city and the worldwide base for Rajneesh.

Sheela, meanwhile, was wrapping up a trip to Australia. There, she badly botched a business deal. Resorting to drugging and eavesdropping, Sheela manipulated her way into partownership of a public company, only to watch its value plummet overnight when word got out. The move cost the commune nearly $1 million.

When she returned to Rancho Rajneesh, she faced incessant demands from the guru to expand his fleet of Rolls-Royces. He wanted to make it into the record books as the man with the most, and it was costing the financially shaky commune $200,000 a month. He also was demanding a $1 million watch, telling her to divert funds from the commune's needs if necessary.

Then, a federal jury awarded $1.7 million to an elderly former sannyasin who hadn't been repaid a loan. During the trial, Sheela sent a team to poison the woman, but the mission failed.

Sheela seethed when she learned the verdict. She felt betrayed by the jury and her own lawyers. The commune didn't have that kind of money.

The road ahead looked bleak. Sheela saw only one way out: murder.

-- Les Zaitz: email him at specialreport@oregonian.com; visit the Rajneesh Report page on Facebook

Rajneeshees in Oregon -- The Untold Story: In 1985, the Rajneesh commune dissolves after death plots and botched assassination attempts target outsiders and insiders alike.

Ma Anand Sheela's gaze swept over the commune leaders seated on the floor before her. She was in an especially dark mood.

"Are you people cowards or are you sannyasins of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh?" she asked.

The day before, a jury shocked the commune by awarding $1.7 million to a former Rajneeshee for an unpaid loan. The judgment was part of ever-worsening developments for the eastern Oregon compound.

Sheela said the verdict showed the Rajneeshees couldn't count on fair treatment from U.S. courts or anyone else. The commune's enemies had to be stopped, she said.

That night, Sheela was an exhausted and nearly defeated woman. For four years, she had done the bidding of Rajneesh, an Indian guru who pressed Sheela to build him an international commune. Sheela chose to do that on a 64,000-acre ranch an hour's drive north of Madras.

Many of those seated before her had helped. The mix this May night in 1985 included the presidents of the commune, its investment corporation and its medical operation. The mayor of the sect's city was there, as were a handful of operatives who had secretly executed most of Sheela's plots.

After Sheela spoke, another leader gave what amounted to a pep talk, supporting Sheela's startling call to action.

One woman raised her hand. "I can't kill anybody, but I support you if you do it." Two men protested that the idea of murder was insane. They were browbeaten as cowards.

Others, startled by Sheela's proposal, kept their qualms to themselves because of growing mistrust among the insiders. The meeting proceeded to identifying enemies for a growing hit list.

So far, outrageous acts hadn't helped the Rajneeshee cause. The secret squads poisoned several hundred people in The Dalles. They set fire to the county planning office. They exploited homeless people, costing Oregon taxpayers $100,000 in bus fare to return them to their cities of origin.

Murder didn't make much sense, either, but the judgment of the leaders was crippled by exhaustion, isolation and their unwavering faith in the guru.

More meetings followed the extraordinary session in Sheela's bedroom, the scene for much of her plotting. She went to the guru for help stiffening the resolve of those participating. She returned with a tape of her conversation. Although the quality was poor, the commune insiders heard Rajneesh say that if 10,000 had to die to save one enlightened master, so be it.

Their top target was Charles Turner, the U.S. attorney for Oregon. His prosecutors were investigating immigration fraud at the commune. A federal mediator disclosed to the Rajneeshees that criminal charges were likely and might include the guru himself. He also disclosed that Sheela probably would be charged.

Sheela thought killing Turner would somehow derail the investigation.

A plan evolved to gun him down on his way home. One of the assassins traveled the country with another sannyasin, buying pistols that couldn't be traced. Others set up a safe house in Portland, which became the base for scouting Turner's home. On one occasion, two assassins sat in a McDonald's in Downtown Portland across from Turner's office, sipping coffee and monitoring his movements. They considered gunning him down in a parking garage but couldn't figure an easy way to escape.

Dave Frohnmayer, the state attorney general, was targeted as well. To determine with certainty where he lived, one Rajneeshee posed as a Bible salesman to reach his front door. Others staked out Frohnmayer's office in Salem.

A team of three went to Portland to kill James Comini as he lay in St. Vincent Hospital, recovering from ear surgery. As a Wasco County commissioner, Comini had been critical of the Rajneeshees, and he kept up his criticism after leaving office.

There was danger for enemies on the ranch as well. Much of the planning focused on killing two of the guru's personal staff: his doctor, Swami Devaraj, and his caretaker, Ma Yoga Vivek. Sheela convinced the others that the two were a threat to the guru. As proof, she played a secretly recorded conversation in which the doctor agreed to obtain drugs the guru wanted to ensure a peaceful death if he decided to take his own life.

The assignment to kill Vivek went to Ma Anand Ava and Ma Anand Su, president of the sect's investment firm and also known as Susan Hagan. The two set out late one night to catch Vivek in her room. They carried an ether-soaked rag to render her unconscious. In anticipation, Su trimmed her fingernails so no flesh would get trapped as evidence if Vivek fought.

The plan was for Ava to inject her with a lethal combination of potassium and adrenaline. They never got the chance because they couldn't unlock Vivek's rear door. They had the wrong key.

That was followed by a more elaborate plan to kill Devaraj, a British doctor also known as George Meredith. The attempt came the morning of July 6, 1985, when the commune was thick with sannyasins visiting for the annual world festival. The venue for the attempt was the massive lecture hall at the ranch, pulsing with sannyasins dancing to pounding music.

Devaraj, sitting cross-legged on the floor, considered joining the dancing. Then, a woman named Ma Shanti Bhadra, also known as Jane Elsea, leaned over his shoulder and whispered in his ear. He felt a hot sting in his buttock. She had jabbed him with a miniature syringe concealed by a handkerchief.

He whirled on her. "Oh, so this is what it's come to, has it?" he asked as he got to his feet. Shanti Bhadra walked with the doctor.

"What's wrong? What's wrong?" she asked in feigned surprise.

Devaraj made it out of the lecture hall and was flown to a Bend hospital. He nearly died from the injection of adrenaline.

The attack was a shock. Up to now, the episodes had seemed like pranks or justified acts of self-defense. But now the Rajneeshees had nearly killed one of their own. The guru himself ordered Shanti Bhadra to be drugged and questioned, an order Sheela ignored.

Ma Yoga Vidya, one of the commune's top executives who was also known as Ann McCarthy, thought other murder plans had been scrubbed when she heard two others discussing the Turner plan.

Vidya had fought Sheela in private about such plans. Sheela brushed aside her concerns but kept Vidya loyal by threatening to kill her husband.

Now, discovering that murder was still part of the operation, Vidya snapped.

She made her way to Sheela's room, interrupting a meeting.

"It's got to stop. I can't stand this talk of killing anymore. I can't stand it. I can't stand it," Vidya said. She collapsed on the floor, convulsing and crying.

Sheela summoned Shanti Bhadra from an adjoining room, asking her to calm Vidya. Shanti Bhadra was the one who had tried to kill Devaraj, and she was assigned to shoot Turner. She snapped when she encountered Vidya.

"I will not be killing anybody," Shanti Bhadra said. "No one will be killing anybody."

The turning point had come, for the commune and for Oregon.

The murder plots ended, as did other dirty tricks. Soon after Labor Day 1985, Sheela quit her posts at the ranch. She fled to Europe with selected taped conversations involving the guru, sect promissory notes and miniature hypodermic needles such as the one used to attack Devaraj. A dozen of her allies also quit the commune, joining her in Germany or fleeing elsewhere.

The ranch quickly fell apart.

At a news conference, the guru described a litany of crimes he attributed to Sheela and her "gang." Both Oregonians and Rajneeshees were stunned.

New commune leaders hired outside lawyers, who questioned sannyasins about what had gone on. The guru told his followers to be truthful. They were unsparing in their recollections.

At the same time, state and federal investigators rushed in, gathering evidence and interviewing Rajneeshees. Soon, two of Sheela's most trusted insiders struck deals. That included Krishna Deva, the Rajneeshpuram mayor, and Ava, one of the key members of the commune's dirty tricks squad.

Both gave lengthy statements that astonished investigators. The summary of Krishna Deva's statement, given over eight days, ran 96 pages.

In the coming months, one sannyasin after another trooped into court, admitting criminal conduct on behalf of the sect. The charges included attempted murder, assault, arson, immigration fraud, wiretapping and conspiracy.

Sheela, nurse Ma Anand Puja and Shanti Bhadra struck deals that included federal prison time.

The guru made a cross-country dash on a chartered jet to escape, but was caught in North Carolina as he was about to leave the country. He was hauled back to Portland in handcuffs, booked into jail like a common criminal. He ordered his lawyers to cut him a quick deal, and he was soon deported as a convicted felon, guilty of immigration crimes.

Courthouses were busy with civil matters as well. Rajneeshee corporations went bankrupt, poisoning victims sued and the state pressed the case against the city of Rajneeshpuram.

The insurance company holding the ranch's mortgage foreclosed, selling the ranch to a wealthy Montana rancher. He later turned it into a camp for Young Life, a Christian youth organization that now brings in busloads of youngsters from throughout the West.

Rajneeshees scattered about the planet, the guru ending up back in India. Renamed Osho, he died in 1990, but the faithful keep alive his spirit, running meditation centers across the world. Elsewhere, some of those most deeply involved faded back into civilian life, giving no clue to their former allegiance to the sect.

Now in Switzerland, Sheela blames Oregonians for much of what happened at Rancho Rajneesh. She'll talk about her days in Oregon, but not her crimes. She doesn't budge when pushed to do so.

"Leave me alone."

-- Les Zaitz: email him at specialreport@oregonian.com; visit the Rajneesh Report page on Facebook

MAISPRACH, Switzerland -- The middle-aged man, his hair tousled, shuffles across the living room in his pajamas.

Sheela Birnstiel rises from her chair, takes him by the hand and guides him back to a seat. He beams at her attention.

Long gone from Oregon and the Rajneeshee commune, Birnstiel remade herself into a successful Swiss businesswoman.

With a compassionate yet direct demeanor, she operates two homes for the mentally disabled. Spite and outrage, her trademarks in Oregon, aren't evident.

Now 62, Sheela appears almost dowdy, dressed in sandals, an unadorned sweatshirt and casual slacks. Her graying hair frames a face plumped by age. Gold-rimmed glasses perch on her nose. She wears no makeup, no jewelry.

Her headquarters is a three-story house on a hillside above the small village of Maisprach, about an hour's drive from Zurich. She and her staff tend to 22 mentally disabled Swiss, ranging from middle age to seniors. The place is spotless, fresh smelling. She cares for another 12 patients in a modified bank building in a nearby village.

Over two days of interviews, Birnstiel -- who remarried in 1984 and was widowed in 1993 -- recounted how she got into the business and how her life unfolded after leaving Rancho Rajneesh. She spoke precisely and openly, until questioned about the darker events in Oregon, including murder plots and arson.

Birnstiel said Oregon shares the blame for the troubles between its residents and the worshipers who believed in the guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. "We had done nothing to them. We legally bought a ranch. We legally went about our work."

She said bigots and corrupt politicians oppressed the sect.

"Have they really followed their Constitution? This is the question I would like answered," Birnstiel said.

She claims criminal acts against the sect went unpunished. As proof, she cited a time in 1983 when a bomb tore into the sect's hotel in downtown Portland. The perpetrator, she said, was let go on $2,000 bail and never tried.

She is wrong.

A radical Muslim was arrested after a bomb went off in his room at the hotel. He skipped out on $20,000 bail but was caught, returned to Oregon and convicted as the commune was collapsing. He served five years in prison, longer than any sentence handed out to Rajneeshees convicted of more serious crimes.

Birnstiel blamed her outrageous conduct on the guru. She only did his bidding. She is candid that she had no interest in spiritual enlightenment, the key draw of the guru. She was instead in love with the man.

"My own personal conflict with Bhagwan was a bigger issue," she said. "My love for Bhagwan had a priority over all problems."

That conflict became irreconcilable in 1985, Birnstiel explained. She said she was told of an order for 400 Valium tablets and learned they were for the guru. She said she was stunned. She had no idea he was taking drugs. He had always preached the need to face life without being intoxicated.

When she confronted him, he got angry, she said. He told her to stay out of it.

She said that same summer, the guru demanded she buy him a $1 million watch. She told him the commune couldn't divert money for that, but he persisted.

Birnstiel said that was the breaking point for her.

"I looked into my soul to see my responsibility," she said. "I decided I cannot compromise."

She said the conflicts between her and Rajneesh, and those with Oregonians, entrapped the women who were her key leaders.

"They were all good people. They wanted to do something for themselves. There were no criminals there," she said. Yet nearly everyone was later convicted of a crime.

Sheela pleaded guilty in the salad bar poisoning case under a so-called Alford plea, where she didn't admit guilt but conceded the evidence could convict her. Sheela took the plea, she said, because she didn't have the $2 million her lawyers said it would cost to fight the charges. She insists she got the better of the bargaining, with prosecutors agreeing to a two-year sentence when they wanted 20.

After prison, Sheela went to Europe, running restaurants in Germany and then Portugal. She fled back to Switzerland and its safety from extradition when she was tipped that American authorities wanted her on new charges.

That was in 1990, and she arrived in the Swiss town of Basel with no money.

The only job a local employment agency could offer was walking a retired man's dog for 10 Swiss francs an hour. She said she took the job and soon became the man's caretaker. That led her to taking three elderly ladies into her own home, the start of her care business.

Sheela appears to have done well. Her staff was respectful, even adoring. Yet Sheela's controlling nature flashed alive, as she directed a couch be moved a couple of inches to make passage easier, and that a nick in wainscoting be attended.

She has published a book about care home management and intends to write another.

Clearly, she remains bitter about Oregon, buttressing her refusal to talk about her own conduct.

"I am labeled a criminal. It is stamped on my forehead," she said. "I have been punished. Leave me alone."

-- Les Zaitz: email him at specialreport@oregonian.com; visit the Rajneesh Report page on Facebook